WORDS . MARCIA L. MASINO

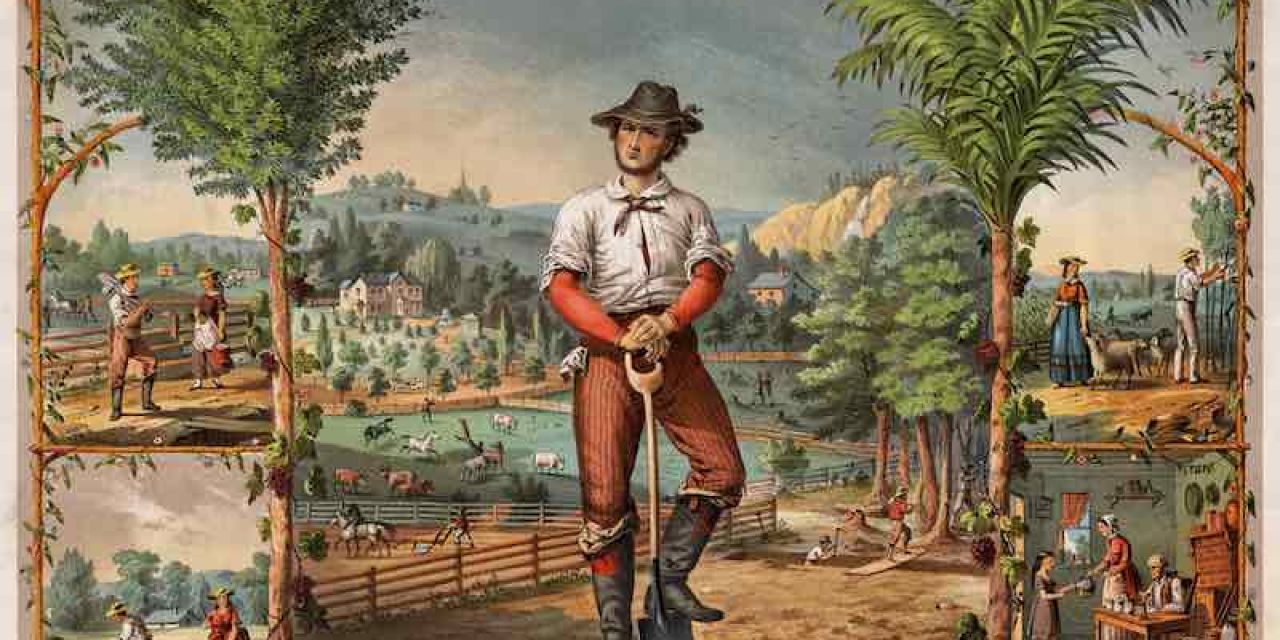

IN 1867, OFFICIALLY KNOWN BY THE GRANDIOSE NAME OF THE NATIONAL GRANGE OF THE ORDER OF PATRONS OF HUSBANDRY, THE GRANGE—AS IT BECAME UNIVERSALLY KNOWN— QUICKLY BECAME THE MOST IMPORTANT VOICE FOR FAMILY FARMERS, A FRATERNAL ORGANIZATION WITH RITES AND OATHS SIMILAR TO DOZENS OF OTHER SUCH ORGANIZATIONS SPREADING ACROSS MID-19TH CENTURY AMERICA, IT WAS A SPEARHEAD FOR A GROWING ANTI-MONOPOLIST SOCIAL MOVEMENT—AN ORGANIZATION REMARKABLY EGALITARIAN AND INCLUSIVE IN ITS MEMBERSHIP AND PHILOSOPHY.

A recent trend, the “back to the land” movement has created new aspiring farmers and artisans who look to the ideals of the farm life of yesteryear. Part of that past agrarian lifestyle was a popular 19th Century Ontario farm organization with secret teachings and rituals known as The Grange or the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry. Quaint and quirky or ahead of its time, the movement’s philosophy deserves another look.

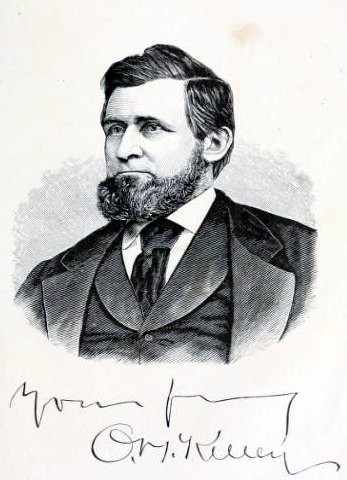

The Grange architect was Boston born, Oliver Hudson Kelley—a New Englander, who had been pioneering in Minnesota, and who later was a clerk in the Federal Bureau of Agriculture at Washington. Biographers also mention that he was an experimental farmer. Associated with him was his niece, Carrie Hil. During Kelley’s travels in 1866 and 1867 to help ameliorate the divi- sion between North and South he came upon countless hostile Southerners with the exception of those who were Masons. Impressed by their reconciliatory kindness he became a Mason and ap- plied the principles he encountered about moral philosophy in action to the agricultural world.

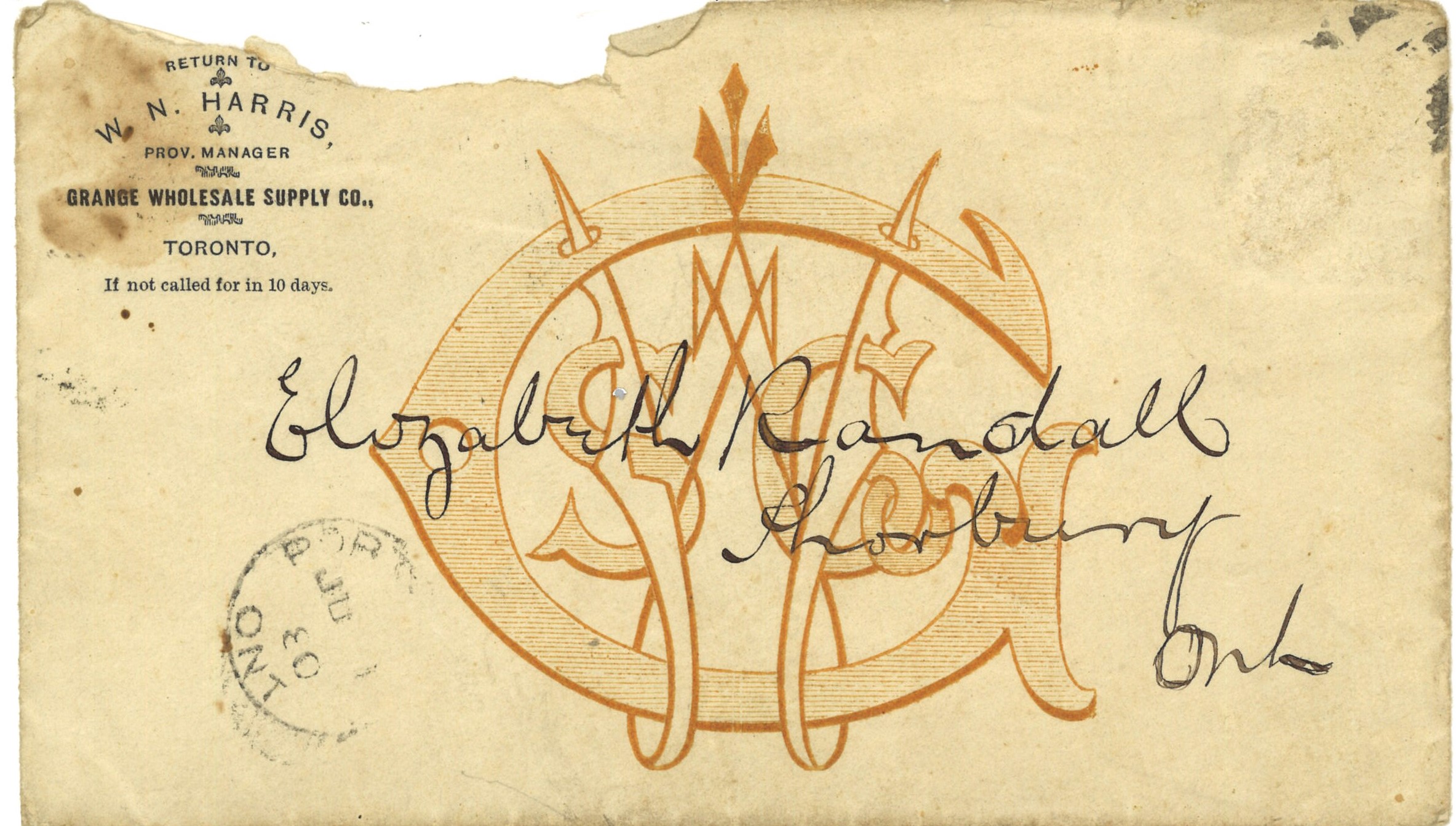

The agrarian organization quickly spread to Canada and became the Dominion or National Grange with many subordinate, provincial and division branches. Some historians state that Quebec was the place of the first Canadian Grange, 1872 London, Ontario became the location of the first lodge. The movement was the predecessor of the Patrons of Industry and the Canadian Farm Alliance.

Bruce and Grey counties were heavily into the Granger movement. One woman played a big role: Agnes Mcphail. Born in 1890 to Scottish immigrant parents, she was one of 12 children who grew up on the family farm in Proton County in the southern part of Grey County. She later became a country school teacher.

Independent, smart and willful she went on to become the first woman elected to Canada’s House of Commons in 1921. She remained in office until 1940, focusing on issues concerning farming, labour, and penitentiary reform. Early on, while she earned her living as a country school teacher in Port Elgin and then in Alberta, she became intensely interested in the national and political issues among farmers and was intensely supportive of the farm movement particularly as it related to women.

As a member of The United Farm Women of Ontario, Mcphail advocated for change. She was described as a radical democratic populist in Terry Crowley’s book, Agnes Mcphail and the Politics of Equality. He goes on to explain, “One of the last areas of southwestern Ontario settled for farming was Bruce and neighbouring Grey County. They had proved fertile for the Grange membership from 1870 onward.“ Organization was begun in Canada by Eben Thompson a 22 year old Vermonter and a graduate of Dartmouth College. The first Canadian units were set up in Stanstead County in the province of Quebec in 1872 and in 1874 the movement spread into Ontario. After considerable discussion over the government of the Order in Canada, a National Grange was set up in Canada on June 2, 1874.

In Simcoe County there was the Knock Grange. In 1871 the first ten members were from prominent agricultural Simcoe families. However, many smaller tenant farmers were also involved. In 1875a division arose between the Knock and the Dominion Grange because the Simcoe members refused to initiate farm labourers and their wives, viewing them as non- farmers. The Knock Grange farmers were eager to ensure respectability and economic status by denying initiation to others viewed as low class. The Knock Grange is known for revealing a significant schism in the movement, one of class distinction.

The main reasons for the popularity of the movement were educational, economic and political. They organized, became political and held office (actually formed a third party.) Grangers held seats in the legislature in 1890.

Nowadays, The Dominion Grange principles and rituals have al- most disappeared. They are buried in a few small booklets with in- structions for initiation held in University Libraries under, “Canadian Agricultural Societies, National Order of the Patrons of Husbandry, 19th Century.”

Notably absent in articles about the movement both past and present are discussions about the heart and soul of the group, the ceremonies and/or the philosophy; they have been judged obsolete or unimportant.

Not all Grangers partook of the rituals, but they were an established part of the regular proceedings. Housed in the library archives is one personal booklet dedicated to the philosophy espoused by the Grangers—it was written in 1886 by a Grey County resident, Mrs. Moffat, from Edge Hill. What makes Mrs. Moffat unique is not only her Edge Hill address but that she wrote her booklet from the standpoint of the three “lady offices” in the organization. She must have taken initiation into the lodge. (Women were always and inherently equal in the Grange Movement.) Her poetic tribute to the Grange’s nature goddess of Flora, Pomona and Ceres were in line with the Initiation teachings.

Tariffs and boundary lines may be more or less of a hindrance to trade but nothing can stop the spread of ideas and it was not surprising therefore, to find that in 1872, the National Grange of the Patrons of Husbandry spilled like a flood across the 19th parallel. ~ Geo. F. Stirling, Publicity Department, United Farmers of Canada, Western Producer – December 8, 1927

A glimpse into what Mrs. Moffat would have experienced… Eventide. The growers could continue for another hour of fieldwork but instead their tools are still. They return to the farmhouse, exchange their work garb for ‘good’ clothing and head to the meeting house to join the other farm folks.

They enter the hall and are greeted by women clothed in Roman Goddess costumes of pink, yellow and green. Beyond them in the center of the room is a small altar with blossoming tree branches, seasonal fruits, carefully tied bundles of ripened grain and bunches of grapes placed upon it. The sheaves of grain echo the emblem of the banner hanging on the wall.

Seats are placed around the room’s periphery. Evenfall, it is time. The Goddess clothed in green speaks and reminds the farmer – initiates of their journey that begins with the springtime seeds of Faith. She holds up ‘simple grasses’. Then, the Goddess Pomona of the fruits continues, “The seeds you plant, flower in the Summer teaching you the lesson of Hope, for the seeds transform through the partnership between the Divine source and your willing hands.” Ceres, the yellow robed Goddess displays sheaves of grain and then exhibits a small replica of a scythe, “We glean for the mind, the body and the soul. Be careful to pick the best seeds from the abundant harvest for your future endeavours. Charity is goodness, share your harvest, your knowledge and your enthusiasm with others.”

Afterward, the women and men have fellowship — they mingle with others members inquiring about farm matters and the progress of the groups’ political projects. Evening has turned into night, time for home and rest before another harvest day begins. The banner of the National Grange of the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry with its grain sheaves symbol is folded and put away.

“THE HISTORY OF THE FARM MOVEMENTS IN CANADA HAS BEEN A HISTORY OF EBB AND FLOW, OF RISE AND FALL, BUT THROUGH IT ALL THERE HAS BEEN A STEADY IMPROVEMENT OF CONDITIONS OF THE MEN AND WOMEN AND CHILDREN ON THE FARMS. – Geo. F. Stirling. Publicity Department, United Farmers of Canada, Western Producer – December 8, 1927