Legends of Creation

Words by Deena Dolan

James Simon Mishibinijima’s artwork weaves a rich array of deep themes stemming from an authentic Anishinaabe perspective—a treasury of wisdom that imparts sacred teachings distilled over countless ages.

ACCORDING TO ANISHINAABE ORIGIN stories, all parts of creation once lived in harmony. Gitchi Manitou (the “Great Spirit”) gathered the four components of Mother Earth—fire, land, air, water—and infused them into a Sacred Megis Shell. Through the fusion of the Four Sacred Elements and Gitchi Manitou’s breath, humanity emerged. The Anishinaabe people sprung forth from this Original Man, shaped in the likeness of Gitchi Manitou, intricately connected with Mother Earth, dwelling in harmony alongside all life enveloping him.

Today, the Anishinaabe consists of three First Nations: the Algonquin, the Cree, and Ojibwe. For over 12,000 years, Anishinaabe artists and storytellers have cultivated a distinct culture of depicting the spiritual and social dimensions of human relations. Their connection to the natural and spiritual realms of the earth is deep and timeless. Everything possesses a spirit, resulting in intricate interconnectedness. Living a good life in the Anishinaabe/Ojibwe way entails embracing the Seven Grandfather Teachings of wisdom, love, respect, bravery, honesty, humility, and truth.

Born in the mid-1950s on Mnidoo Mnising (Manitoulin Island), James Simon Mishibinijima was inspired as a boy by generations of these long-respected Anishinaabe/Ojibwe stories, traditions, and experiences, emerging as one of Canada’s foremost artists. Mishibinijima means “Birchbark Silver Shield,” but missionaries who found his birth name difficult to pronounce changed it to James Alexander Simon. He has since reclaimed Mishibinijima.

His small but proud community of Wikwemikong, one of the few Unceded Territories in Canada, was tiny—just 34 houses—and steeped in the legends of the Ojibwe people. The territory’s website declares: “We have not relinquished any of our rights to any of the lands in the Great Lakes Basin to any Nation. We continue to govern the waters, air, and lands including Islands, as our ancestors have since time immemorial.”

James’s neighbor, artist Francis Kagige, encouraged James to begin painting as a child and to actively seek the knowledge of the elders. Kagige, one of the first generation of Manitoulin artists, became known as one of the new Woodland or legend-painting artists, following the lead of Norval Morrisseau, who introduced Ojibwe art to the world. Ten years later, The Indian Group of Seven emerged, comprised of Morrisseau, Kagige, Jackson Beardy, Alex Janvier, Eddy Cobiness, Carl Ray, and Joe Sanches. The mainstream art world finally recognized the importance of First Nations artists.

As a young man, James’s works quickly became sought after by collectors, and he gave back to his birth community by teaching his craft to students in Wikwemikong, educating them about the importance of learning their heritage, language, and the Seven Teachings of the Grandfathers. When he was just 17, however, a serious single-car accident left James in a coma for three days. Thankfully, his physical recovery was quick, but interestingly, his connection to his spiritual surroundings became even stronger. He recalls the images he experienced—he went to “a place”—there was a foggy light, clicking sounds—and a voice that said, “Not yet.” Following that near-death incident, his visions became stronger, clearer, and more present, and his positive outlook on life has never wavered. DaVic Gallery of Native Canadian Arts notes, “Mishibinijima’s uplifting philosophy has struck a chord with people who seek solace in the midst of tragedy and meaning in a world that is often confused and frightening.”

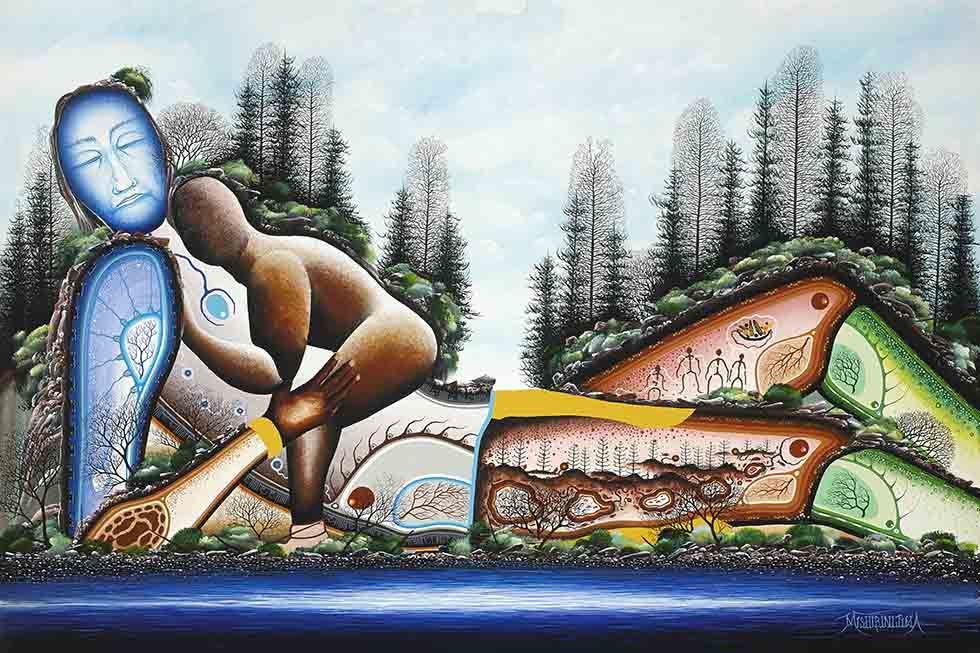

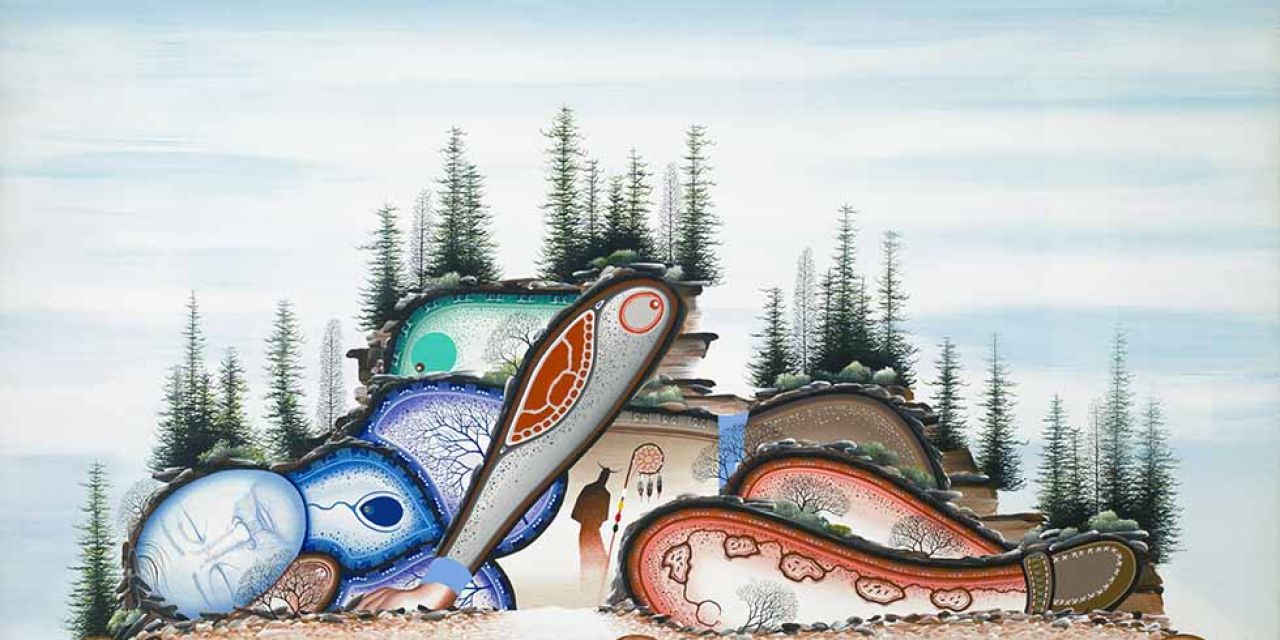

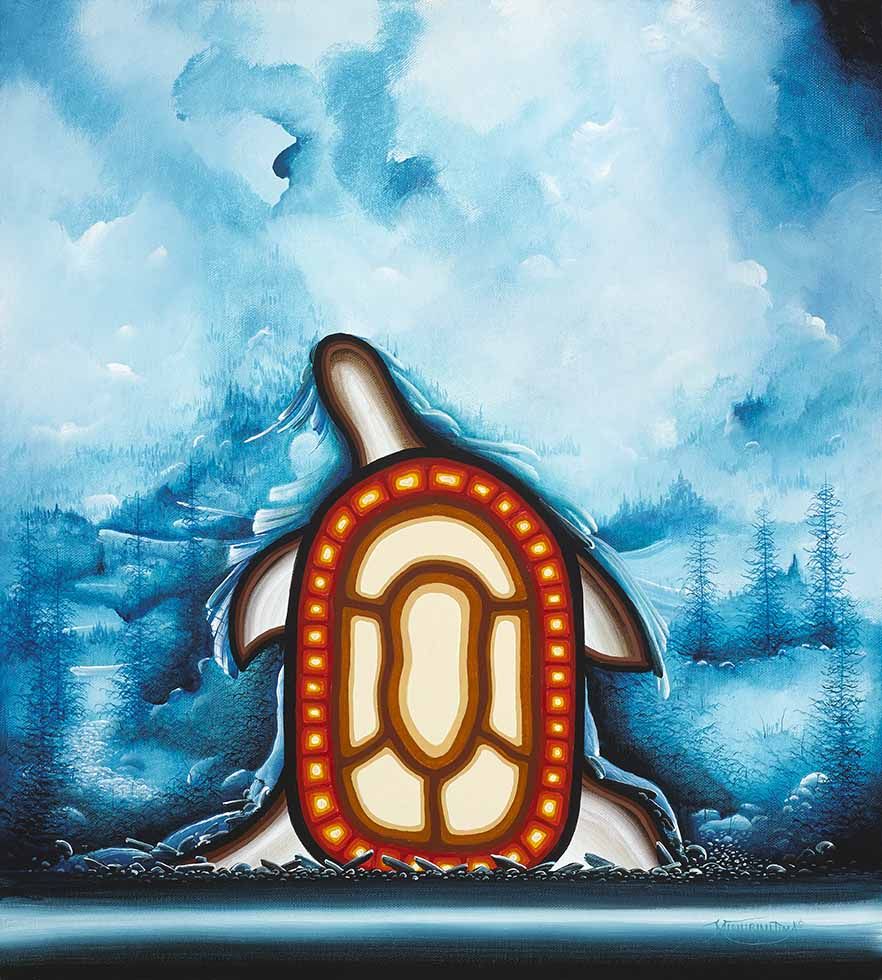

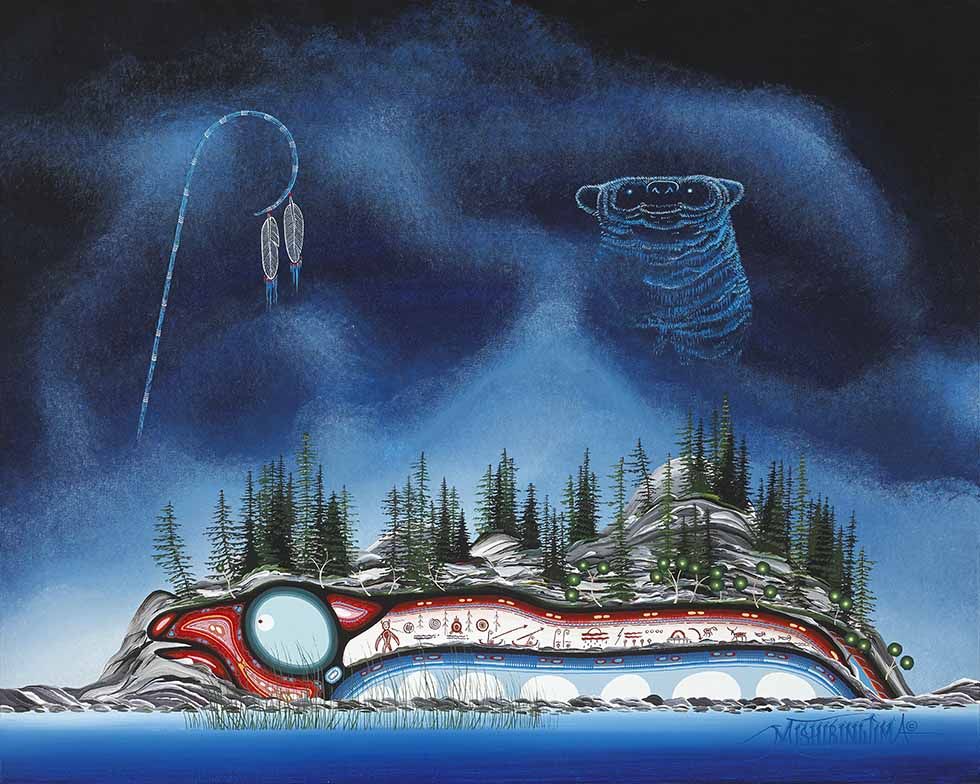

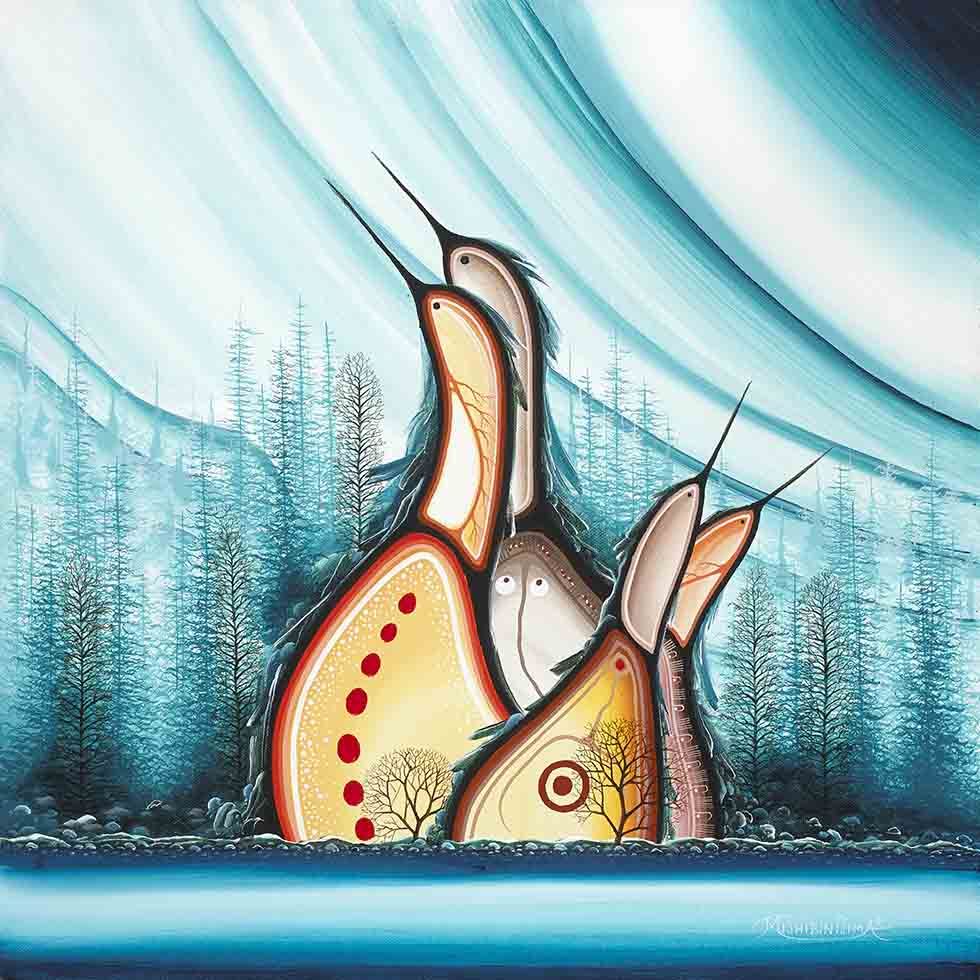

Often described as belonging to Woodland art, James’s paintings explore relationships between spiritual energy and symbolism, blended with traditional legends and myths. His visions, when transcribed onto his canvases, contain multiple, complex details. One single work will contain images within images, formed by strategic applications of thousands upon thousands of acrylic hues. Filled with powerful meanings and deeply spiritual symbolism, his paintings relay an intricate story that envelops the viewer. The longer one looks, the more one will see. James’s works take time to produce—one painting might take a year to complete. “I believe that Woodland art can promote healing and understanding amongst all of mankind. Colour, I believe, is a power that the creator gave us to communicate traditional values and teachings. Ojibwe culture is alive and well as long as we express it in a good way.”

James’s artistic journey embarked on a global trajectory when he was just 19 years old. The local Ojibwe Culture Association recognized his talent and included him as a member of a delegation sent to an international exhibition in Rome.

Two signature styles are attributed to James: the most celebrated is his iconic, sought-after Mishmountain series, which portrays various settings on and around Manitoulin Island. These captivating acrylic works meld humanity with nature, wherein his uplifting philosophy offers solace to those grappling with adversity. He extends hope and spiritual sustenance to a world often muddled and foreboding. Aligned with his Anishinaabe heritage, he implores us all to nurture our land, safeguard our natural environs, value our earth, and preserve it for our offspring. “His most common theme is painting islands and water because a human being is an island and his inner universe is made out of water; destroy one part of who he is, and it will mean he will destroy himself forever,” says Dan Graham.

A second personal style adapts ancient pictographic paintings that convey sacred teachings distilled over thousands of years using visual symbolism. This perspective is echoed by the DaVic Gallery of Native Canadian Arts: “These symbols communicate the legends of creation, man’s place in creation, the ethics of human behavior, the story of nomadic migrations, and the sacred poetry of the Anishinaabe language in graphic form. He remains true to the meaning of these forms and the knowledge of the rich spiritual iconography of the societies known as the Three Fires Confederacy of Manitoulin. Mishibinijima brings ancient teachings to the modern world and continues the role of the Anishinabek painters.”

When asked about artists whose work he admires, James’ immediate choice is Daphne Odjig (1919-2016), a highly accomplished Ojibwe artist also from Manitoulin Island. He knew her and appreciated her works that emphasized Native family life and relationships, the impact of colonialism on the Indigenous population, and human suffering.

Over the decades, James has been the recipient of many first and best-of-show awards at international art exhibitions. He also develops curriculum materials for First Nation schools and continues to amaze art collectors with the detail and intricacy of his canvases. His work is found in galleries, museums, government, and corporate buildings in Canada and beyond. James has released three books: “Pictographs – The Graphic Art of James Simon Mishibinijima” (2017), “Indian Residential School Paintings” (2019), and recently he has collaborated with Dan Graham on a soon-to-be-released book: “Seven Grandfather Teachings – a journey to self-healing,” which features stunning paintings based on the traditional Seven Grandfather Teachings. E

For more information on James Simon Mishibinijima, visit Mishart.ca