TAKE EVERYTHING AS IT COMES

Words by Aidan Ware, Director and Chief Curator, Tom Thomson Art Gallery

Among Canada’s artistic luminaries, Tom Thomson stands unparalleled. His extraordinary talent, profound bond with nature, and distinctive artistic approach, has left an enduring imprint on Canadian art, inspiring generations of artists.

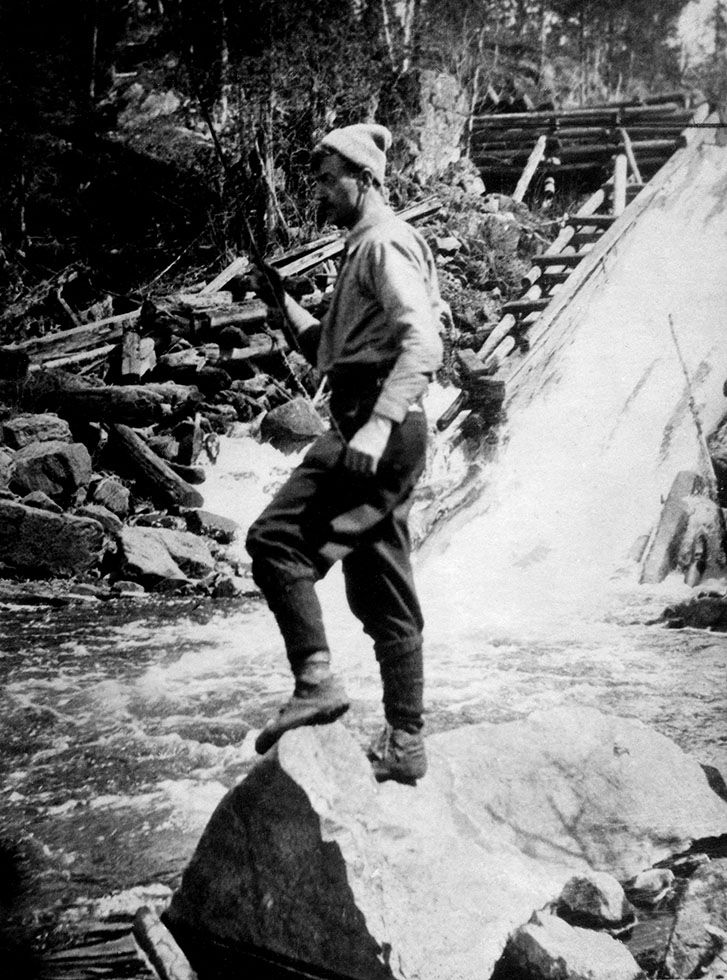

It’s impossible to think of Canadian art, or even Canada, without Tom Thomson. But who was he really – this mythic figure, this artistic iconoclast who completely defied and revised the artistic traditions and ideas of his time so fearlessly, so breathtakingly, so beautifully, and in such stunning fashion? Who was this man – standing like a Heathcliff in his plaid jacket, smoking his pipe, ceaselessly and passionately steering his canoe toward the farthest back wood, back bush, bush whack place where he could bear down his brushes to incarnate some magnificent thing he saw, some outrageously true moment in time, maybe just as the sun came up or set itself down, or as the light caught fire in the trees or as the shadows settled into napping forests? Just who was this guy?

We may never truly know Tom. Who he loved, what his thoughts were, if he truly enjoyed too much butter on his mashed potatoes, or even how he died. The only true thing we will ever come to know of him is through his body of work which is an extraordinary legacy that he has left for us.

Tom Thomson’s story begins in the small town of Claremont, Ontario, where he was born on August 5, 1877. He was the sixth of 10 children born to John Thomson and Margaret Matheson. Within months of his birth the family moved to Leith, 11 kilometres northeast of Owen Sound. It was here, by the shores of Georgian Bay, that Thomson grew up. He displayed an early affinity for nature and artistic expression. His innate curiosity about the world around him, coupled with an insatiable desire to capture its beauty, laid the foundation for his future artistic endeavors.

Thomson had a rootless start to adulthood. He unsuccessfully enlisted for the Boer War in 1899 due to health reasons and then apprenticed as a machinist at Kennedy’s Foundry in Owen Sound for eight months. He briefly attended the Canada Business College in Chatham before relocating to Seattle, Washington, to join his brother George at his business college. This is where he became experienced in the craft of lettering and design, working as a commercial artist. By 1905 he returned Canada to work as a senior artist at Legg Brothers, a photo-engraving firm in Toronto. Throughout these years, as he sought his path in the world, Thomson continued to return home to visit his family which had moved to Owen Sound.

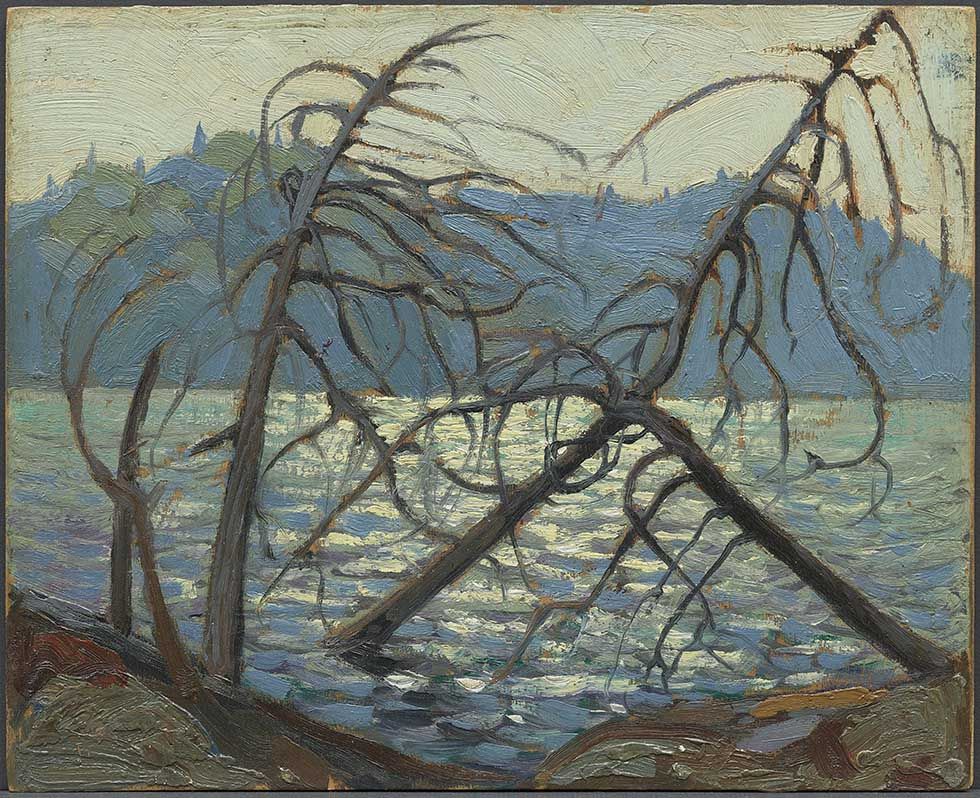

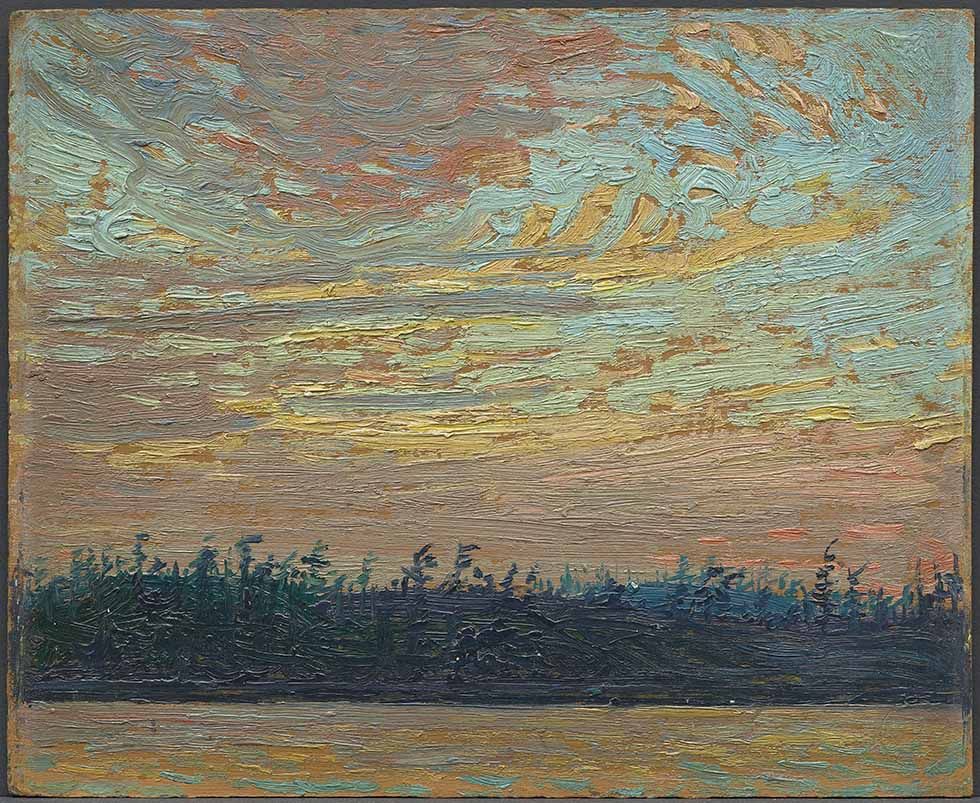

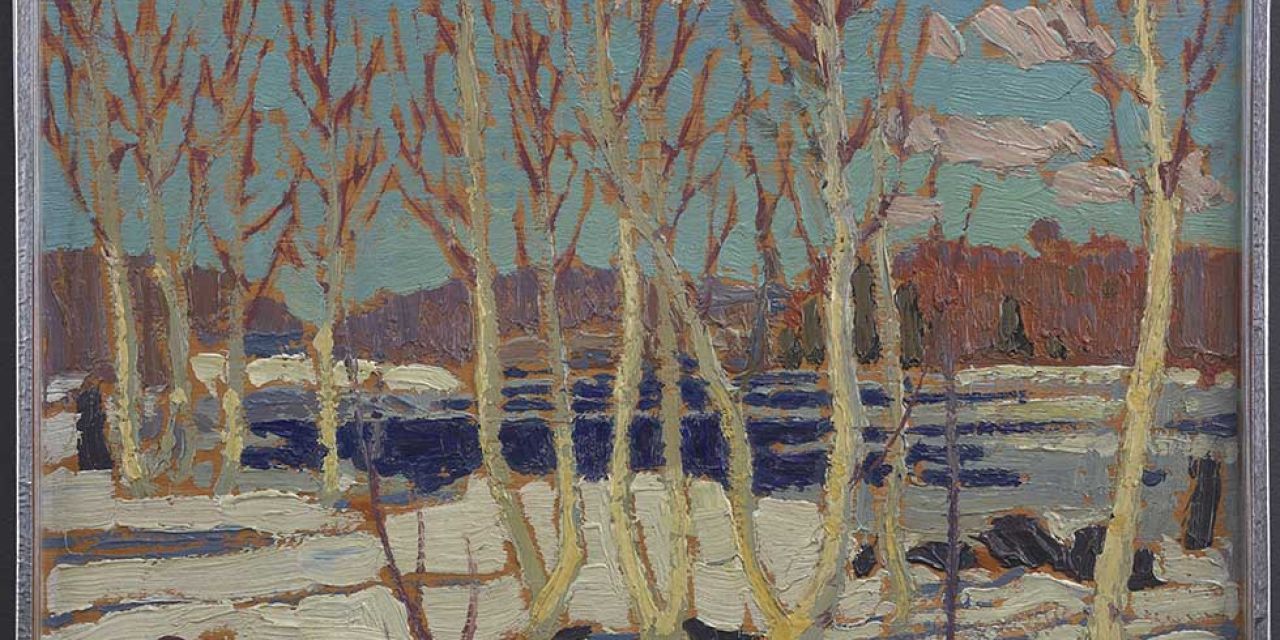

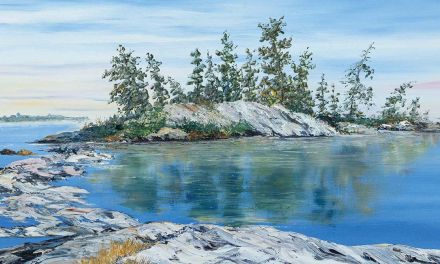

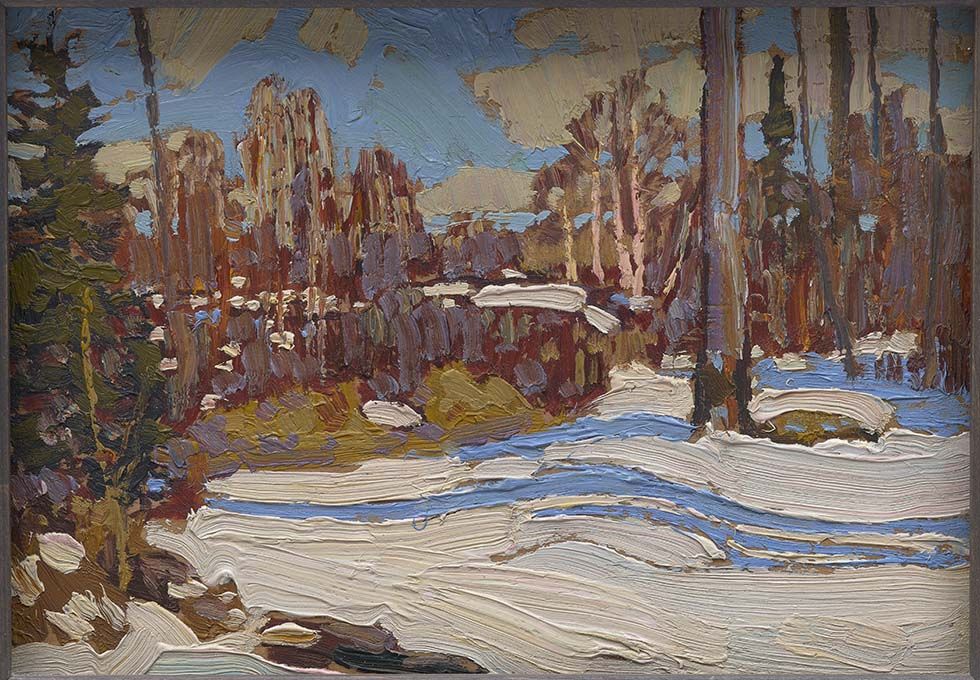

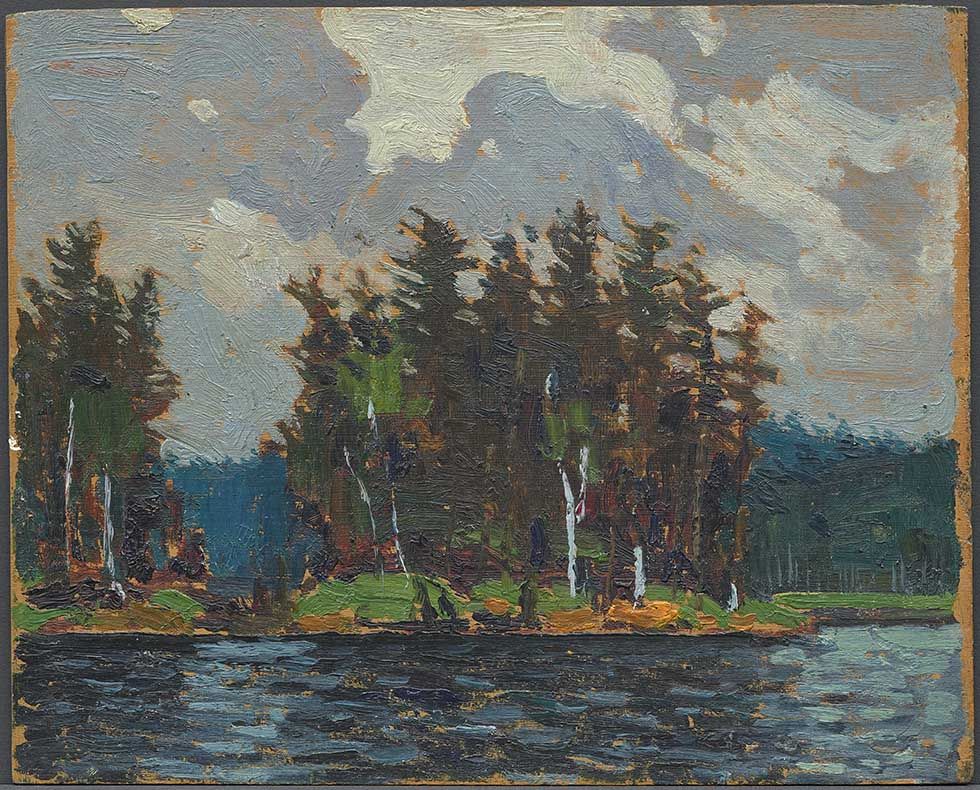

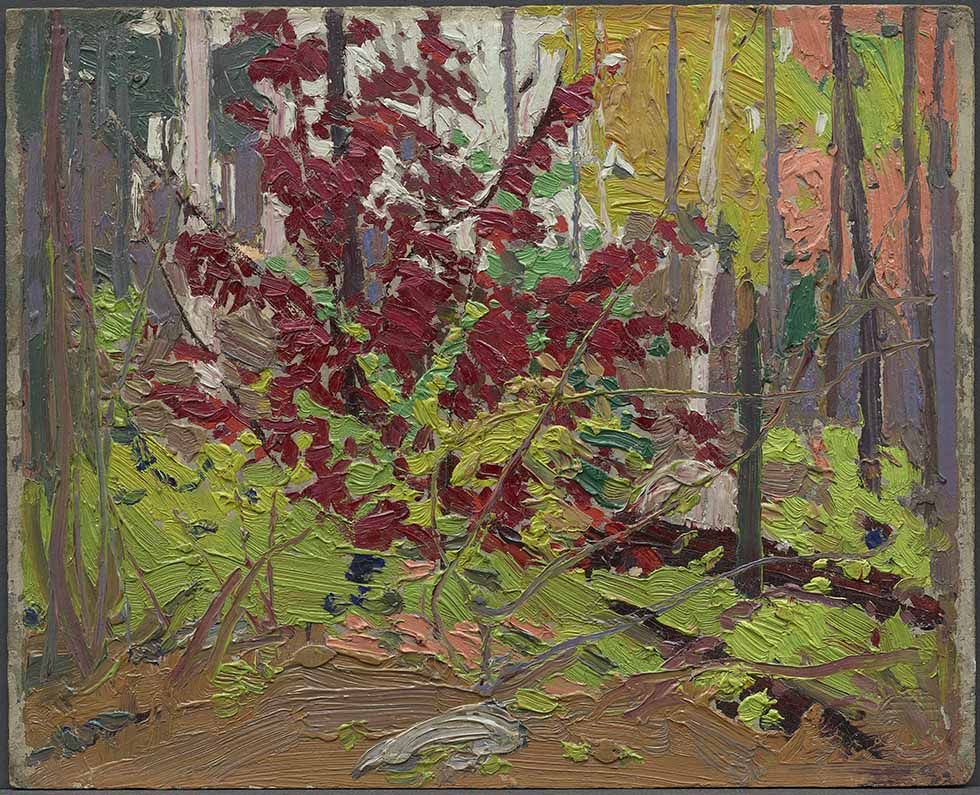

Throughout his time at the Grip, Thomson constantly lusted after the wilderness of Algonquin Park, with its sprawling expanse of pine forests and moody lakes where he would race to capture the mesmerizing seconds of dramatic dawn or dusk skies, or the moments when cumulus clouds would codify into a mass of white epiphany, or the seconds when the sun turned a thicket of dogwood or sumac into the lead stars of some passionate and unknown drama. It was here where he truly found himself, and his artistic form, internalizing and extrapolating the lonesome landscapes, distilling them into icons of impossibly beautiful, saturate, climaxed incarnations of nature and emotion. By 1915, Thomson was living in Algonquin Park from spring to autumn acting as a fishing guide and fire ranger. It was here that he found the impetus and subject matter to create an unequivocal body of work that at its core, dominates Canadian art history.

Tom Thomson’s legacy in Canadian art is multifaceted and profound. His bold use of color, innovative brushwork, and reverent connection with nature set a new standard for Canadian landscape art, one that would profoundly influence the style and philosophy of the Group of Seven after they officially formed in 1920. His paintings, characterized by their dynamic compositions and vivid colour palettes, continue to captivate people from all over the world. His paintings have become symbols of identity, gracing the walls of institutions, public spaces, and even currency notes. The powerful evocation of landscape through unconventional uses of colour and broad actionable brush movement, forged and articulated a new connection between people and the land.

Thomson once famously said: “Take everything as it comes; the wave passes, deal with the next one.”

As a steward of Thomson’s legacy, I think about Tom every day. Every morning when I unlock the Gallery door and every night when I lock it, I sense his presence. His paintings, once merely images, have transformed into a deeper resonance, creating a sense of unconditional belonging. I don’t just see them; I feel them. They are in this way, a part of us all—part of our identity fabric, our community and national consciousness. They are not pictures; they are talismans and teachers and touchstones. They are somehow spiritual and somehow worldly all at the same time and once experienced, they exert a metaphysical kind of power through which Tom’s abiding presence remains singular and clear.