Leafield of the Algoma Steamship Company, lost November 9, 1913, in Lake Superior with Captain Charles Barker and crew. Built at Sunderland, England, 1892. Collingwood Museum Collection, X968.759.1

The Great Storm of 1913

Script by Ken Maher, Stories from Another Day,

a Collingwood Museum Podcast Historical photos courtesy of the Collingwood Museum

In the deadliest event in the history of Great Lakes Navigation, a four-day storm, referred to as the “White Hurricane”, struck with relentless force in November 1913. Wind gusts reached over 140 km/h, and waves measured over 11 metres high. The storm left in its wake 19 vessels lost and an estimated 248 sailors killed. The exact number will never be known.

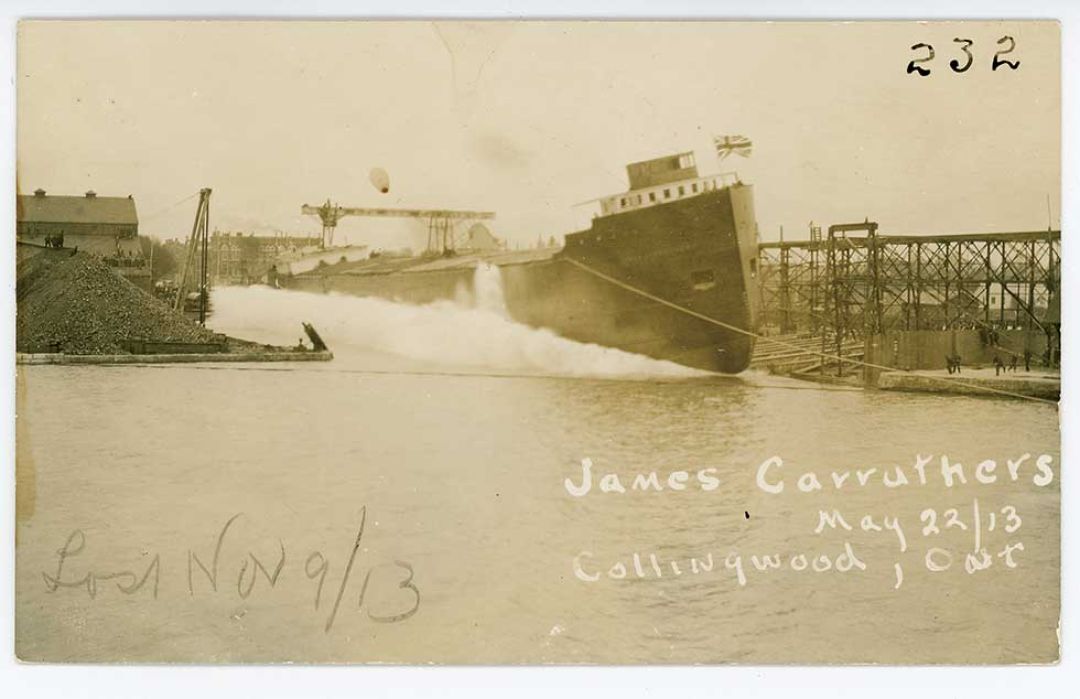

“WE BREAK AWAY from our regularly scheduled programming to bring you the following news bulletin: The SS James Carruthers, the ‘Pride of the Lakes,’ launched only five months earlier from the Collingwood shipyards, has sunk off of Goderich. Now confirmed, twenty-four men lost, two from Collingwood: Watchman Bob Stone and Wheelsman Joe Simpson. Stay tuned to this station for more news as it becomes available”.

The day is Wednesday, November 12th, and the news is finally confirmed by the Canadian Press—news that would prove relentless in its grief and loss, as the full weight of the tragedy became known. The Great Lakes Storm of 1913, historically referred to as the “Big Blow” the “Freshwater Fury” or the “White Hurricane”, among other names, was a blizzard with hurricane-force winds that devastated the Great Lakes Basin from November 7 through November 10, 1913. The storm was most powerful on November 9, battering and overturning ships on four of the five Great Lakes, but Lake Huron was particularly hard hit.

“This just in, it is now confirmed the SS Regina wrecked at Point Edward. Twenty lives lost, including Second Mate Tom Doyle of Collingwood.”

So, what on earth had happened? As the USGenNet Great Lakes Maritime History website describes, on Sunday, November 9, after two days of fierce storms, the low-pressure system was receding from the lakes, and in numerous areas, the snowfall had ceased while the barometric pressure was on the rise. Ships departed from the safety of the ports, guided by captains who likely thought the storm had mostly dissipated, understanding that profits couldn’t be made by staying in port when the weather took a minor turn for the worse. Little did they know that they were on the brink of facing the deadliest storm ever recorded in the history of Great Lakes navigation.

Divers explore the wreck of the SS Wexford, photo by Fraser Penny.

SS Wexford, photo by Fraser Penny.

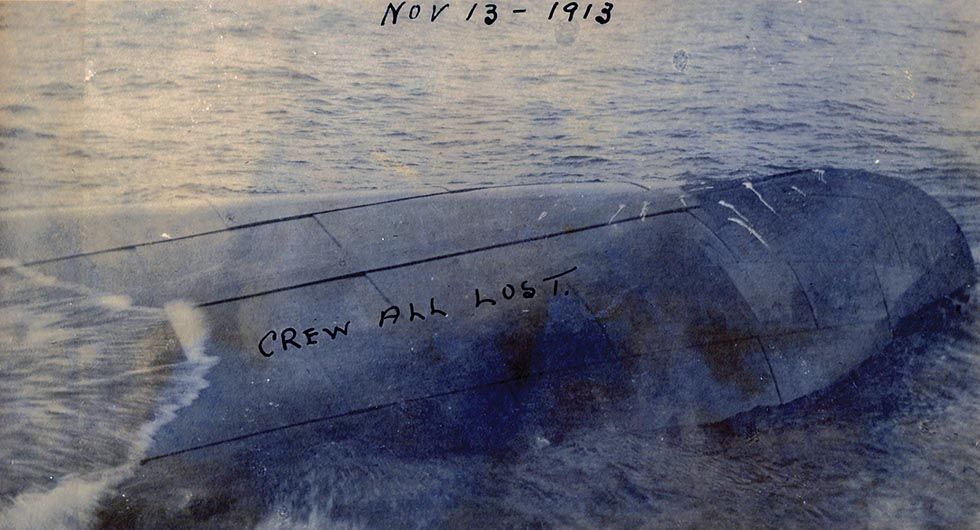

Charles S. Price floating bottom up in Lake Huron. Crew all lost. Collingwood Museum Collection, X974.357.1.

Near forty ships, over two hundred men Sailed the lakes when the storm began They fought the wind And the mountain waves But never came home again These good ships torn By the claws of the storm And the white foam smothered the crew And the wreckage washed On the shores of the lakes When the deadly gale was through

Gale of 1913 – It’s Quiet Where They Sleep by David O. Norris & Dan Hall

“Sources this afternoon are reporting the SS Wexford foundered and sunk off St. Joseph Island, taking Captain Bruce Cameron (a local hockey hero) and seven other Collingwood mariners with her. Among them Chief Engineer Jim Scott, Watchman Orrin Gordon, Second Mate Archie Brooks, Steward George Wilmott, and his wife Stewardess Grace Wilmott.”

The USGenNet Great Lakes Maritime History website goes on to say that what wasn’t known at the time the Great Lakes shipping resumed was, “A second low-pressure system had formed overnight to the south and was missed by the morning weather report. By the time the evening weather report was sent the storm had almost a full day to build strength. Barometers plummeted as the storm intensified to hurricane proportions, its counter-clockwise winds shrieking as the monster pounced, raking its icy claws the length of Lake Huron. Hurricane strength winds of 90 mph drove blinding snow and sleet, piling waves into roaring black 40-foot mountains that mauled vessels and shorelines. Giant freighters were coated with sheets of ice; hurled against rocks and land as though nothing more than children’s bathtub toys by deafening winds that screamed from one direction while mountain sized waves smashed at them from another. The greatest devastation of all was felt when twelve vessels lost their battle with the storm, going to the bottom with every soul aboard.”

“The SS Leafield was also lost just outside of the Soo—17 Collingwood men were listed among the dead. Captain Charlie Baker, Chief Engineer Andy Kerr, First Mate Alf Northcote, Assistant Engineer Tom Bowie, Second Mate Fred Begley, Stewards Robert and Lorne Sheffield (brothers), Firemen Charlie Brown and John Munro, Wheelsman John Barrett, Watchman Bob Robinson and George Pierce, deckhands Billy Shakespeare, Bob Whitelaw, Ovilia Peteau, and Mike Tierney.”

And so, the terrible news kept coming, again and again… pounding in and shattering homes and families as sure as the waves had devastated all those vessels. Yet even in the overwhelming grief, there was some good news. Captain WC Jordan of Collingwood drove his ship, the SS Franz, into the teeth of the storm and somehow managed to pull into Collingwood’s harbor two days overdue and badly battered. But he was still afloat, and all the crew was accounted for. Jim McCutcheon, the first mate on the Wexford, was onshore in Detroit sending a money order home when he was delayed and late in getting to the ship, which left port without him. This delay would save his life.

Analysis of the storm and its impact helped lead to better forecasting and faster responses to storm warnings, stronger construction (especially of marine vessels), and improved preparedness among the destructive natural disaster to hit the lakes in recorded history, the Great Lakes Storm of 1913, killed more than 250 people, destroyed 19 ships, and stranded 19 others. The financial loss in vessels alone was nearly $5 million. This included about $1 million in lost cargo totaling over 68,300 tonnes. No other in recorded history has been so terrific in force, covered such an extended area or continued with sustained high wind velocity for such length of time.

But ask anyone in Collingwood what the real loss was, and they could give you name after name after name. Of the 27 Collingwood men lost, only five bodies were ever recovered to be laid to rest here at home. The others were taken by the waters they had worked on. Schools, stores, and factories closed down for the mass funerals held a week after the storm. And the cost this town would bear meant that it would be a long time before any family here in Collingwood could look at the water or listen to the howling of a winter storm in the same way again. E

Ships Lost

Argus, Charles S. Price, Henry. B. Smith, Howard M. Hanna Jr., Halstead, Henry B. Smith, Hydrus, Isaac M. Scott, James Carruthers, John A. McGean, L.C. Waldo, Leafield, Lightship No. 82, Major, Matoa, Plymouth, Regina, Turret Chief, Wexford

* Table of Losses [From Lake Carriers’ Association Annual report 1913]

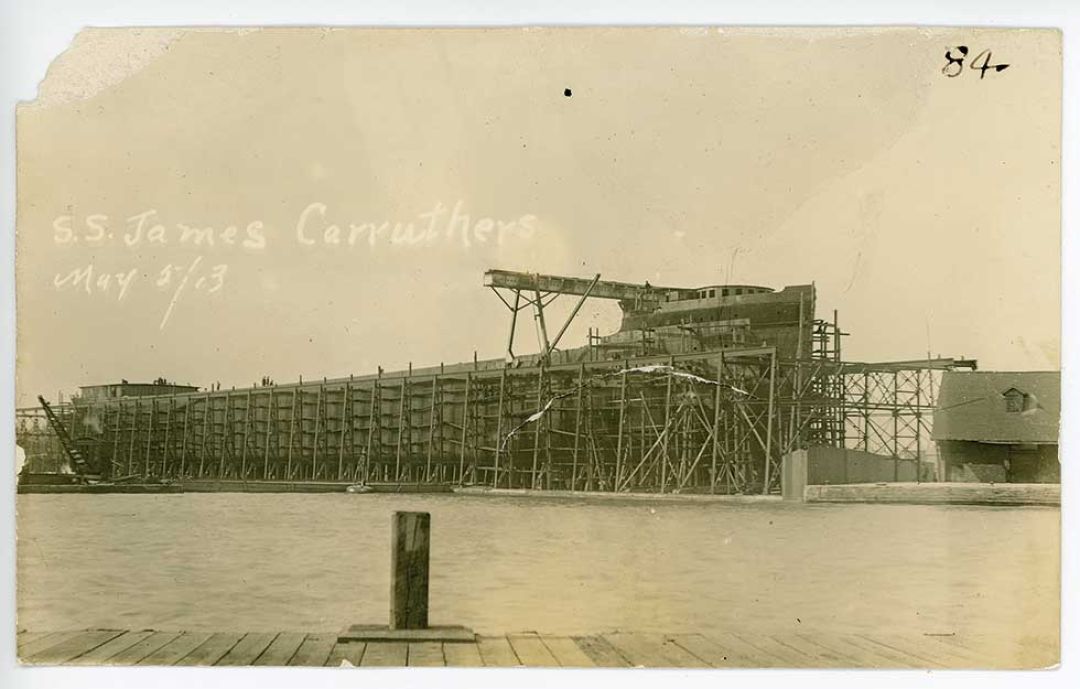

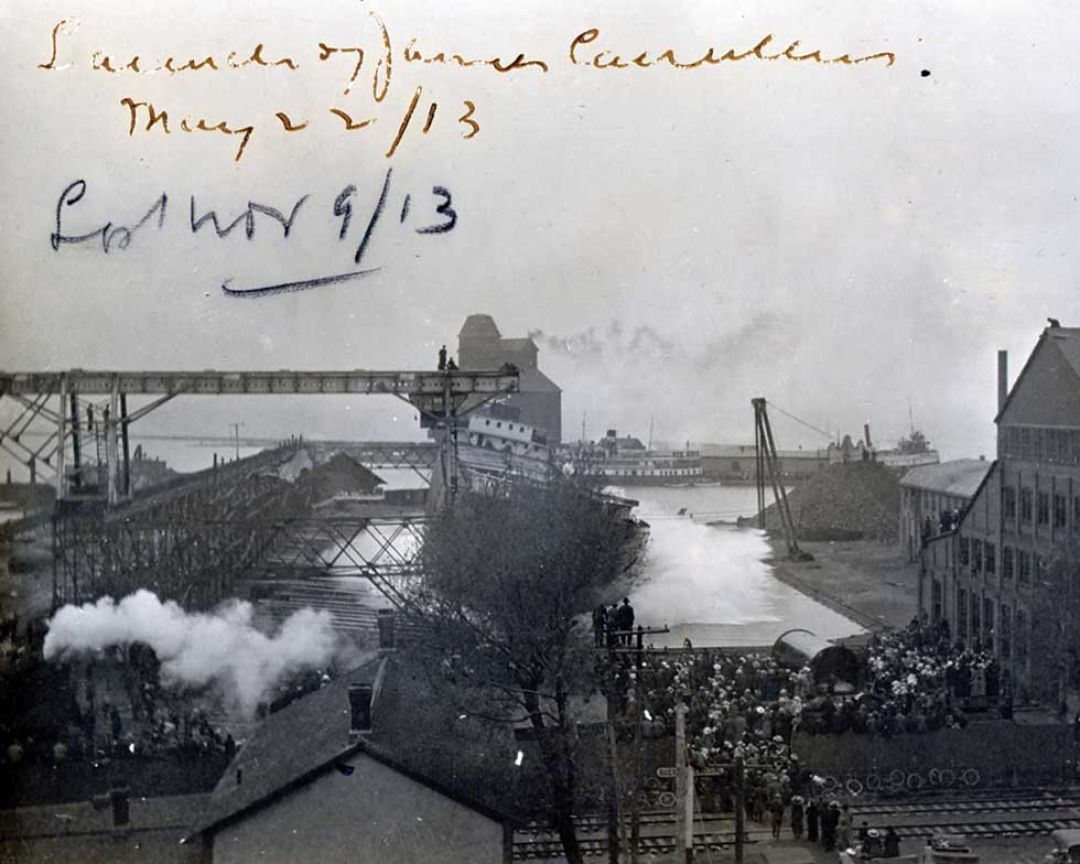

SS JAMES CARRUTHERS

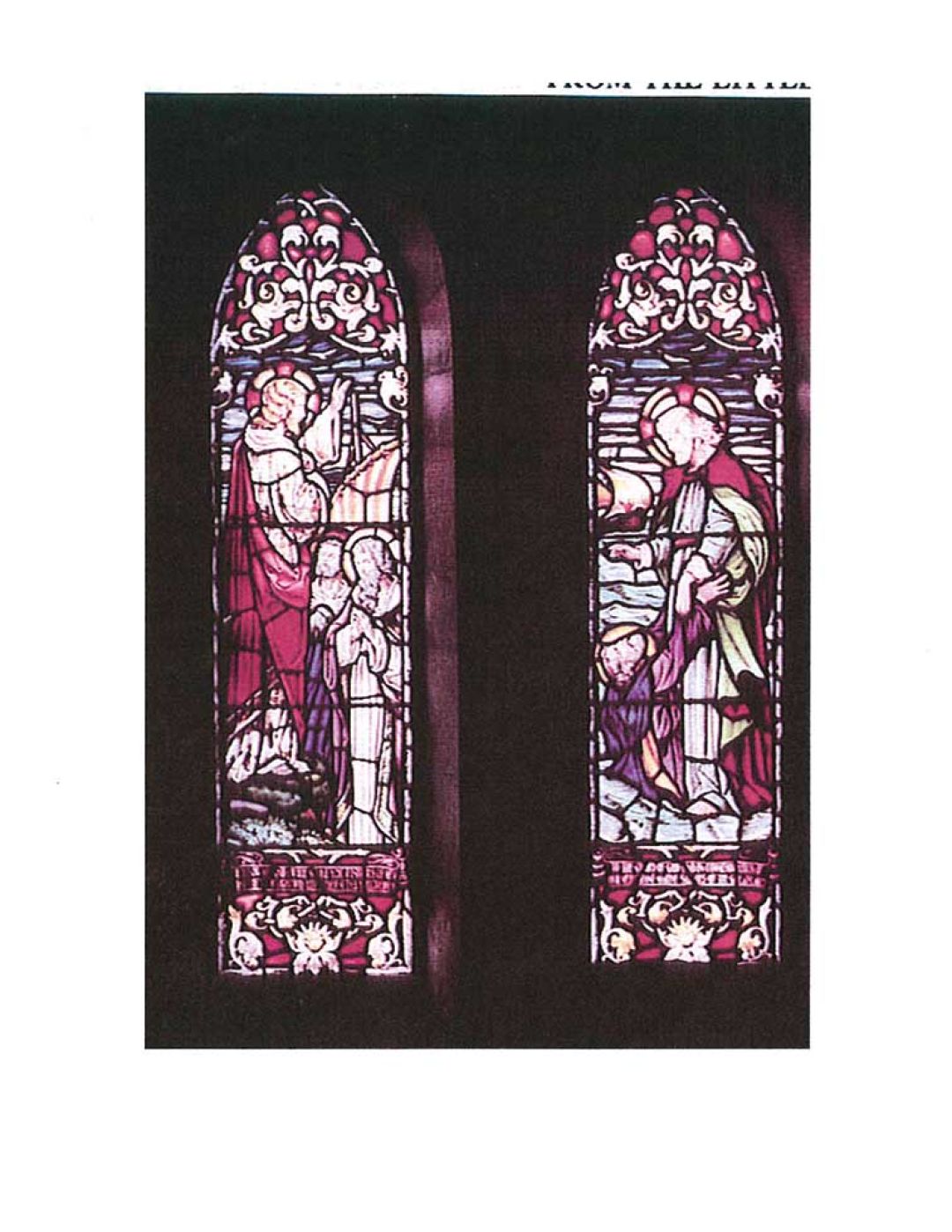

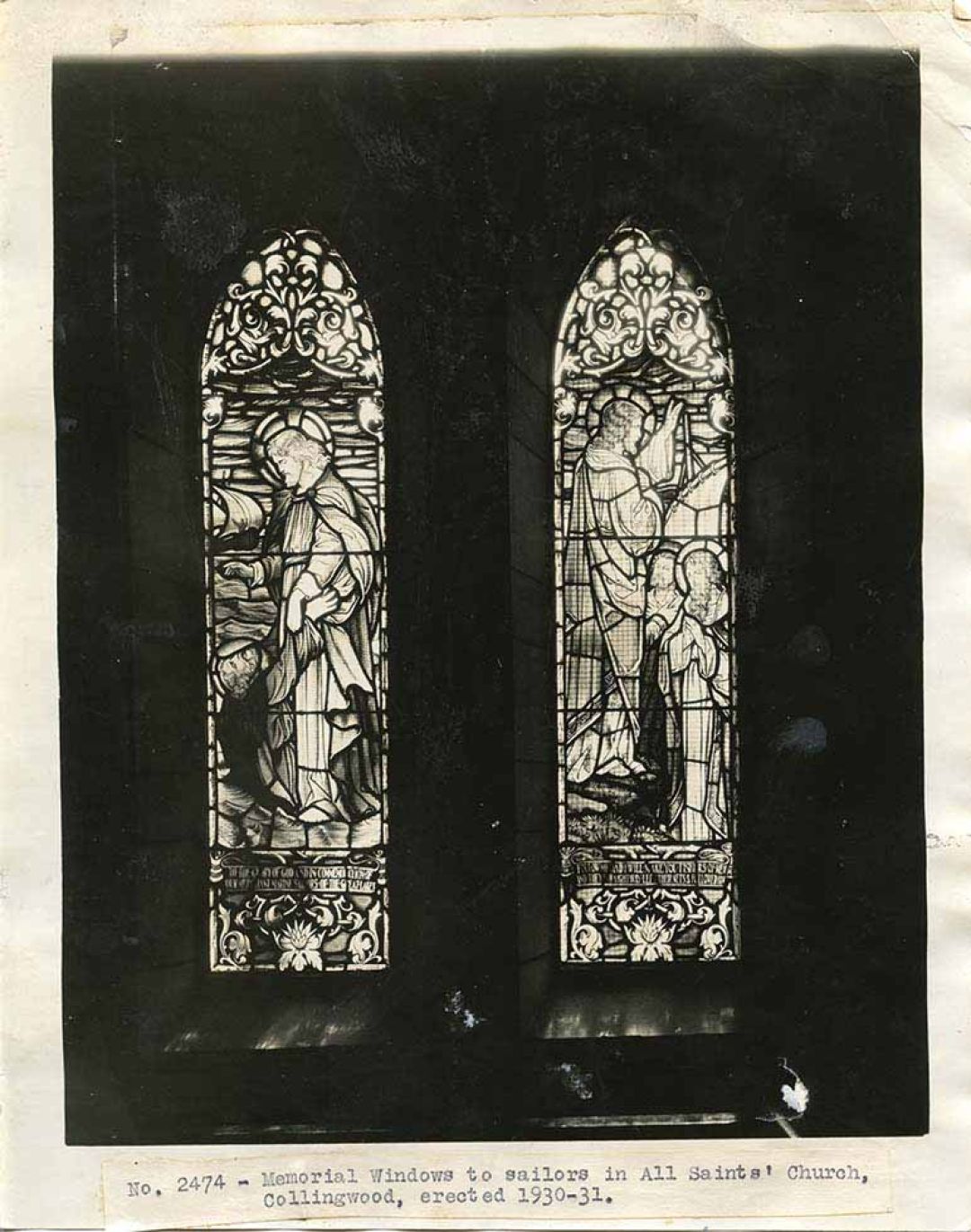

Known as the “Pride of the Great Lakes”, the SS James Carruthers launched from Collingwood only five short months before she went down in the Great Storm. Her loss was certainly a tough blow to those who had built and invested in her, but the real pride of the lakes was the hard-working men and women who made their living in these often-dangerous conditions. And it was because of that pride that those who lost their lives were memorialized in a very special window that is still, to this day, available to be seen in All Saints’ Anglican Church on Elgin St in Collingwood. If you join them for their worship one Sunday you will be able to have a look or if you call them up and nicely ask, I am sure they would welcome the opportunity to show you.

SS WEXFORD

After being lost for 87 years, the SS Wexford was finally discovered on August 25th, 2000, resting intact and upright in 75 feet of water off the shores of Grand Bend, Lake Huron. This steel-hulled, propeller-driven cargo ship, which was constructed in 1883, has varying accounts of the crew lost, with numbers ranging from 17 to 24. At the time of its sinking, the ship was carrying a cargo of 96,000 bushels of wheat. To honor the crew on the 100th Anniversary