The Last Lightkeeper

Words by Cara Williams, Photos courtesy of the Johnston family and NLPS – Originally published in the SUMMER 2022 issue of Escarpment Magazine

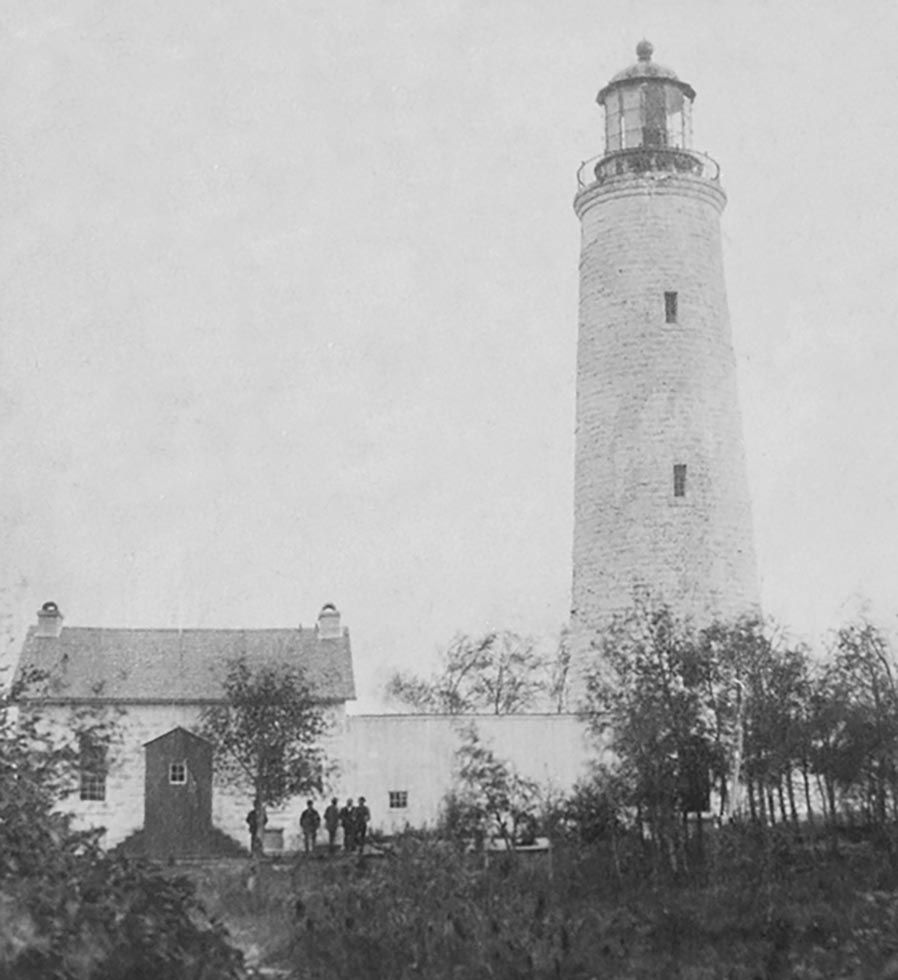

In 1851 Collingwood was established as the northernmost terminal of the Simcoe and Huron Railway line—an integral stretch of track that linked the burgeoning port city of Toronto to ports on the upper Great Lakes. Constructed between 1855-1858, the Nottawasaga Island Lighthouse is one of six nearly identical Imperial Towers built by Scottish stonemason John Brown, to establish safe navigation routes along the coastal waters of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. Its erection marked the beginning of Collingwood’s formative years as a major commercial shipping port.

Standing 85 feet tall and built with whitewashed local quarried limestone, the Nottawasaga Island Lighthouse was first illuminated in 1858. The ornate red copper roof, adorned with bronze lionheads, represents the highest quality mid 1800s coppersmithing. The intricate lantern room was imported from Paris, France, including the state-of-the-art Fresnel lens. This cast-iron composite lens featured intersecting prisms that concentrated the light into a powerful and parallel beam—developed by the French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel, the Fresnel lens was dubbed, “The invention that saved a million ships”. The Nottawasaga Island Lighthouse would remain lit for 124 years, during which time 15 full-time lightkeepers would care for the light and the waterways that surround the island.

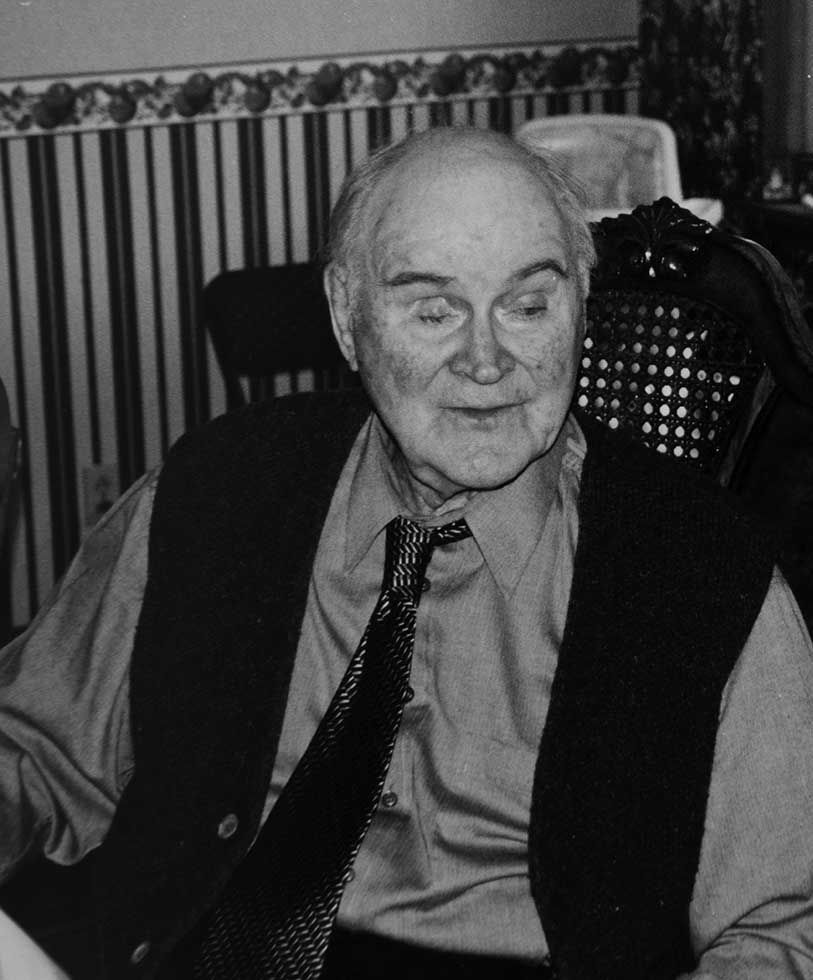

Wilfred Neil Johnston was born in Sunnidale Township in 1917. In the 1930s the Johnston family purchased Telfer’s Point in Collingwood (known today as Rupert’s Landing and Lighthouse Point). Here, Wilfred spent his childhood tending to the family business, Beacon Glow Point Cottages. The closest mainland access to Nottawasaga Island, Wilf (as he was known to family and friends) developed a love for the tall, elegant Imperial Tower that stood upon it. The beam was reportedly so bright that he was able to paint the exterior of a cottage at midnight by its light. Wilf continued to hone his waterman skills as a young adult, building wooden boats by hand, trawling and navigating the waterway between Craigleith and Collingwood. It’s not surprising then that he was approached by the Canadian Coast Guard to take on the role of lightkeeper of the Nottawasaga lighthouse in 1962. Perhaps more notable than his two decades as keeper of the light is the fact that Wilfred lost his eyesight in 1940—22 years before accepting the position. His 20-year service began in 1963 with a starting salary of $11.00 a week.

“My grandfather was 23 years old, and only two-weeks married when he worked in Johnston’s harbour store,” says

Chris Johnston. “He was fixing a fridge and Freon splashed into his eyes, blinding him. He had several surgeries, but nothing helped.” Several of Wilfred’s grandchildren still reside in the Collingwood area, including Chris and sister Leanne Johnston Stephens. “He moved to Collingwood when he was two,” remembers Leanne. “He made his own boats and was always sailing them. Before he took the position as lightkeeper, a government boat would go back and forth from Collingwood and tend the light. But my grandfather knew the lake and the waters so well, despite the fact that he was blind, he was an obvious choice.”

During the first hundred years of the Nottawasaga Island Lighthouse, the lightkeepers were required to reside on the island for up to nine months of the year. The era of resident keepers living on the island ended in 1958 after a fire severely damaged the keeper’s dwelling—the last three keepers, including Wilf, maintained the light and navigational aids from the mainland.

Chris and Leanne have fond memories of their childhood at Beacon Glow Point Cottages. “Since the age of five, I spent all summer there with my grandfather,” says Chris. “He played a ton of instruments—accordion, saxophone, clarinet. We used to sit out at campfires on the water and he’d take requests from the cottage renters. He could do anything.” Wilf’s duties with the Canadian Coast Guard included anchoring channel markers in the spring and collecting and storing them in the fall. He also maintained two inner and two outer range lights. “He knew exactly which lightbulb went in which buoy,” says Chris. The fuel supply for the lighthouse was delivered by ship in a bank of four, four-hundred-pound bottles of acetylene. Wilf hauled the tanks manually by rope into the base of the lighthouse. The light was automated by this point, but Wilf was responsible for tending to it and when necessary, he operated a foghorn by hand on the island. “Sometimes he’d call us for dinner with that foghorn,” laughs Leanne. The lighthouse lantern was checked every night through binoculars from his cottage on shore. “We were like his eyes,” says Chris. “He was always asking us, ‘Is the light on? Is the light on?’ As I got older I would run him out there in a boat. He would climb the ladder, feel around, take the bulb out and replace it. You wouldn’t know he was disabled in any way—it didn’t stop him from doing anything.”

By all accounts Wilf was a capable and vastly skilled waterman. “I remember one time we were out fishing and the boat swung around and the net got caught in the boat’s propeller—it was freezing cold and here’s a blind man with a knife in his mouth, stripping down to his underwear and jumping overboard. He went under the boat—a long way down in very cold water—he cut away the net and came back up, teeth chattering. He never said a word about the cold, just put a towel on himself and got on with it. It had to be done, and he was always the guy to do it.”

The Nottawasaga Island Lighthouse is associated with several dramatic rescue efforts, most notably lightkeeper Captain George Collins’ role in rescuing survivors of the Mary Ward steam ship disaster in 1872. “If ever there was an emergency, the police would call the cottages,” says Chris. “I remember going out on a few rescues with him in the middle of the night. We’d have flashlights and we’d lead the police boats through the bay—he knew where every rock was, even in the dark. I don’t know how many times we saved people stranded on the island, or from boats that hit rocks and sank.” Leanne adds, “His hearing was exceptional. He would hear people in the night and get up and rescue them. He was always calm, always kept his head about him.”

After 50 years of blindness, Wilf received the first of three eye transplants in the late 1970s. “The operation was a success at first,” says Chris. “And he read everything he could get his hands on. Although he was on anti-rejection drugs, the first transplant only lasted about two years. He had another operation a few years later but it didn’t last very long that time. The third time he received a pig’s cornea—only the second person in Canada to have this done—and it wasn’t as successful as the other two. He was in his late 80s by then and decided to just live with it.”

Upon his retirement in 1983, Wilf was honoured with a plaque from then Prime Minister of Canada, Pierre Trudeau. In 1986 the bulk of the Johnston family property was sold to developer Rupert Bronston who built condominiums along the 18 acres of Collingwood waterfront, known today as Rupert’s Landing and Lighthouse Point.

With the arrival of satellite-based radio navigation systems, the Canadian Coast Guard deemed the Nottawasaga Island Lighthouse redundant in the summer of 2003. In 2004 the tower was struck by lightning, causing significant damage to a large section of the exterior masonry and putting the structure at risk of collapse. Recognizing the need to preserve the tower from enduring further decay, in 2015 the Nottawasaga Lighthouse Preservation Society (NLPS) was established and sought to take steps to mitigate any further degradation—the lighthouse was subsequently included in the 2016 National Trust of Canada Top 10 Endangered Places List. Permission was obtained from the Federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans to wrap the exterior of the structure in a weather resistant material that prevented water penetration to the limestone masonry. Today, the NLPS is working to acquire ownership of Nottawasaga Island. Their ultimate goal is to reconstruct the lightkeeper’s residence (a fully restored lighthouse keepers house exists at the nearly identical Chantry Island Lighthouse near Southampton) and restore the elegant tapered form of the lighthouse.

Their mission is to ensure that this irreplaceable marine heritage resource—which has been a steadfast on Nottawasaga bay for over a century and a half—is protected, appreciated and enjoyed for generations to come.

For 124 years the care of the Nottawasaga Island Lighthouse was entrusted to 13 men and two women. The longest keeper of the light, Wilfred Neil Johnston passed away in his 95th year, surrounded by friends and family in Collingwood. He is remembered and beloved by all who knew him, including his six grandchildren who still reside in the area. “He built 13 wooden boats,” remembers Chris Johnston. “One for each of the original cottages on his property. When I was 12 or 13 he told me to pick one—he said he wanted me to have one. I still have it to this day.”

The Keepers of the Nottawasaga Island Lighthouse 1859-1983

Captain George F. Collins (1859 – 1890)

Captain Arthur George Clark (1890 – 1903)

Sarah Clark (1903 – 1904)

John F. Burmister (1904 – 1911)

James McNabb (1912 – 1913)

Anne McNabb (1913 – 1915)

Thomas W. Bowie (1915 – 1924)

Thomas Edward Foley (1924 – 1932)

Samuel Neally Hillen (1933 – 1942)

William “Scotty” Hogg (1943 – 1952)

James A. Keith (1953 – 1956)

James F. Dineen (1957 – 1959)

Ross White (1960 – 1961)

Harry Ward (1962 – 1963)

Wilfred Neil Johnston (1964 – 1983)

The Imperial Towers

Six nearly identical light stations around Georgian Bay and Lake Huron, constructed by Scottish stonemason John Brown.

Christian Island Lighthouse

Nottawasaga Island Lighthouse

Griffith Island Lighthouse

Cove Island Lighthouse

Chantry Island Lighthouse

Point Clark Lighthouse