Steam engine at Collingwood Station, looking north, 1937. Collingwood Museum Collection, X970.414.1

Off the Rails

Script by Ken Maher, Stories from Another Day, a Collingwood Museum Podcast

Photos courtesy of the Collingwood Museum

From its vibrant beginnings as a railway hub to the eventual silence of the tracks, this is the story of how a humble settlement became intertwined with the iron veins of the Canadian railway, leaving a legacy that still echoes through the trails of Collingwood today.

A small crowd has gathered there on the platform. They are listening intently to an older man by the name of Daniel Webster Watson. He had come from Beeton just for this day, even though at his age, travel was not so easy anymore. “Let me tell you about the first time I rode this line,” he says. “It was 1877, and I was just a young fella…” His voice trails off into the noise of the crowds as several families make their way down the side of the train. It is not very hard to see that they are the wives and children of railway workers here to mark the day with their husbands and fathers.

It is then that Conductor Jack Latimer, himself an old timer, steps up on the train and calls out in his well-practised voice that pierces through the noise, “All Aboard!” For a short while, there is a cacophony of sights and sounds as some, but certainly not all, of the people gathered make their way onto the train. And then, in all too short of a time, the passenger train whistles and puffs away from the station… for the last time. The silent crowd remains behind, standing on the platform and watching until the train is out of sight.

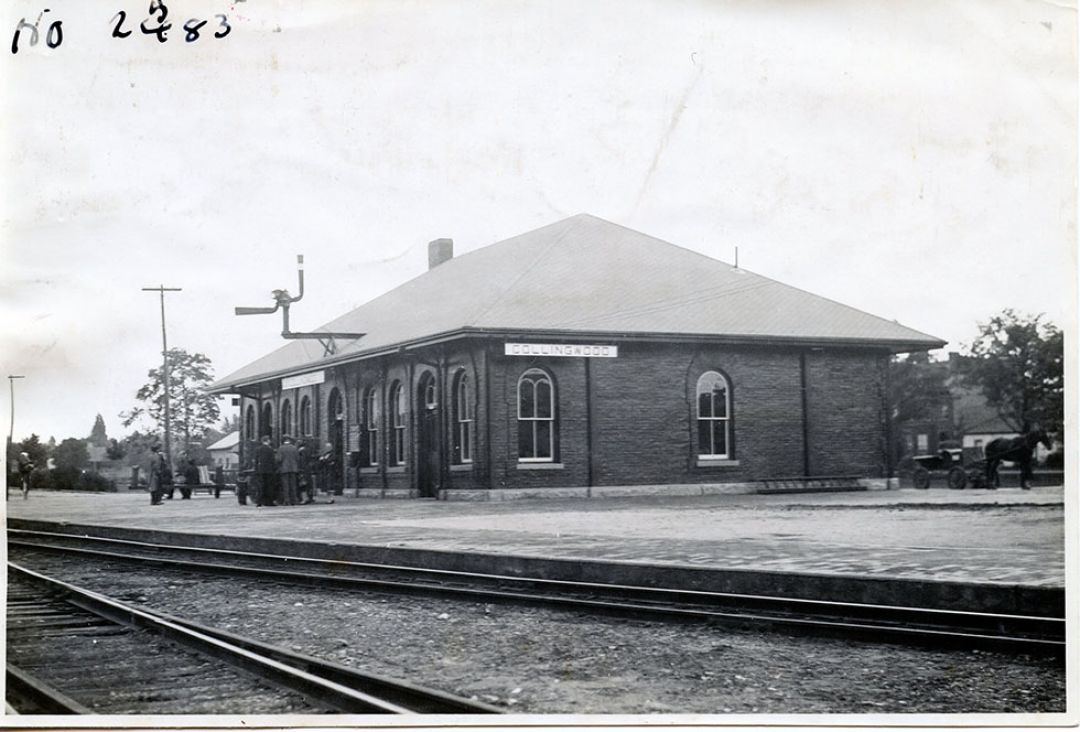

The historic station property, looking south from Huron Street, between 1923 and 1932. Collingwood Museum Collection, X2009.125.1

It was July 2, 1960. The day that passenger trains ceased operations in Collingwood, marking the end of a century-long era of continuous service. Although this day was undoubtedly difficult, it was merely the start of a gradual and inevitable decline. Over the next fifty years, the railway presence in Collingwood would steadily diminish until it disappeared completely.

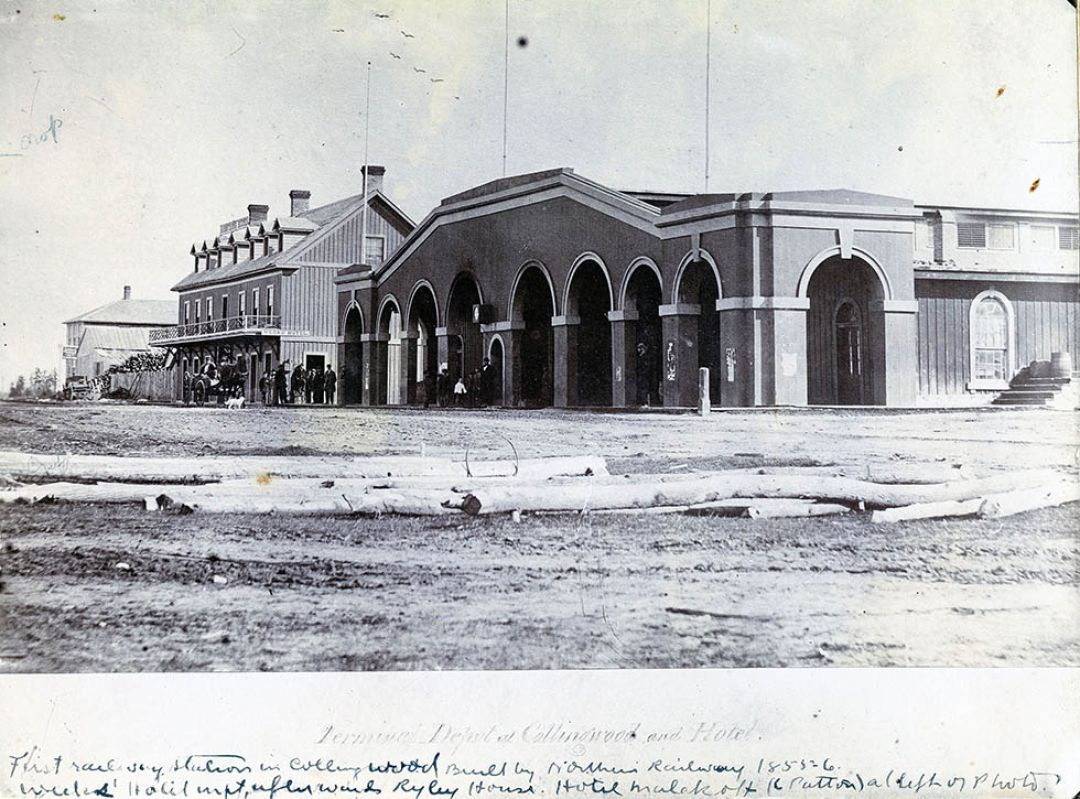

But how had it come to this? Especially when this town was literally built because of the railway. Local historian Isabel Griffin tells us that at the time of its construction, the Collingwood Train Station rivalled Toronto’s own train station, both in its size—being able to accommodate up to five trains at any one time—and in its architectural charm, being influenced by Spanish designs. Indeed, there were more than a few who preferred our end of the line to that in Toronto.

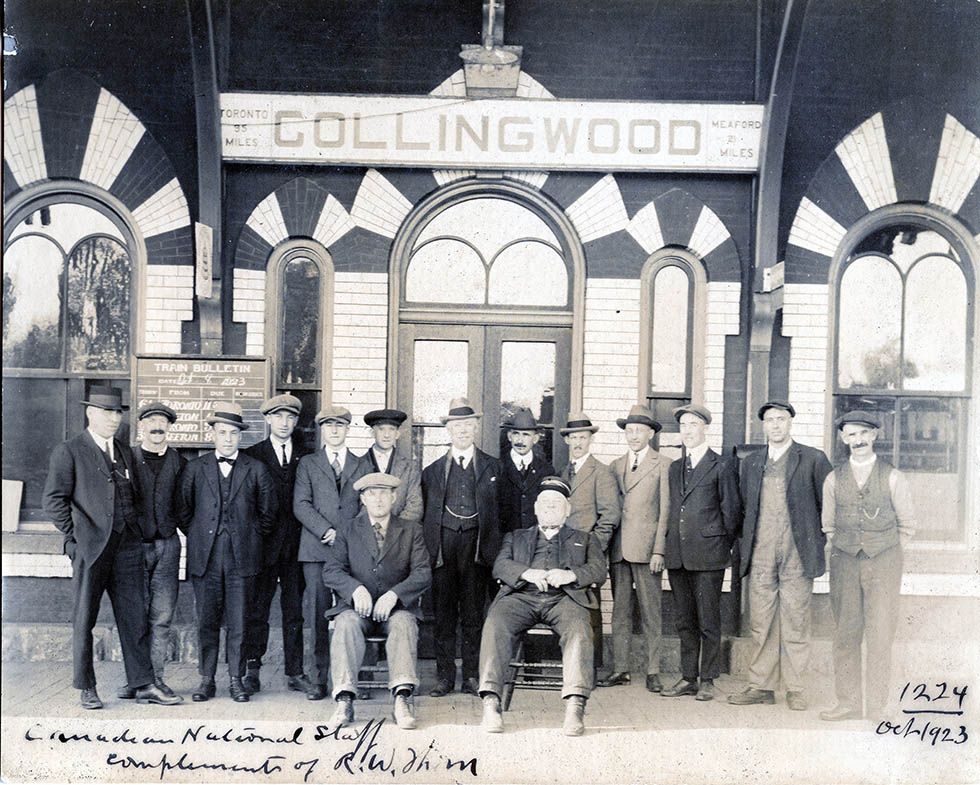

Canadian National Railway staff in front of Collingwood train station, October 1923. Collingwood Museum Collection, X972.142.1

Skiers unloading at the Craigleith train station.

Collingwood Museum Collection, 988.7.3

Before the railway arrived, the closest village in this area was called Hurontario Mills (roughly where the waterworks stand on Raglan Street today). The Collingwood downtown centre we know today was little more than a dense cedar swamp back then. There really wasn’t much going for it, except that by 1853 the powers that be had decided a train line was needed to connect Toronto to Southern Georgian Bay. In actuality the idea had been floating around since 1830. After years of surveying this area, the railway workers had decided the gradient to Penetanguishene was going to be a problem, as was the shifting sand at the mouth of the Nottawasaga River. So, while Penetanguishene had the better natural harbour and Wasaga Beach had easier access, our town site didn’t have their problems, and that became the deciding factor. It also didn’t hurt that starting from an empty slate, anything needed could be built to suit their purpose.

But one of those things that would have to be built was… well… a town! If the railroad was to come through this part of the country, then better infrastructure and a larger town to support it would be the first thing needed. So, when the news broke that the terminus of the railway would arrive here, the building blitz began in earnest. As detailed in Stories from Another Day Season 1: Episode 11, “Fair Play”, land sales exploded, as did the prices. This led to price gouging and some dirty politics. Yet as all the new building came in, some of the old bits of the pre-existing settlement went away. One local character, Collingwood Harris, reluctantly closed his beloved cedar bark hotel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, as the town underwent transformative growth and change. But he would end up doing just fine in the new economy when instead he… well, that is a story for another day.

Looking north towards the harbour from the wooden platform at Collingwood’s train station, c. 1874-1900.

Photographer, James Asa Castor. Collingwood Museum Collection, 007.19.6

Apart from the unusual structures, there were other changes necessary for our community to welcome the arrival of the train. Alongside the surge in construction, a more dignified name for the town became imperative. Up until that point, the area was known as Hen and Chickens Harbour. An apt, if not rustic, appellation. The story retold in several sources suggests that while the area was being surveyed for the terminus of the rail line, the name Collingwood was suggested by one of the four members of the team of surveyors. The name was given in honour of Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, victorious in the battle of Trafalgar after Lord Nelson died. The party of four, the story goes, christened the harbour with the new name right then and there, with a bottle from their lunch, and without asking anyone who lived nearby what they thought of the idea. But somewhere along the way, the name stuck.

But times changed, as they always do. Unlike the sudden advent of the railway in Collingwood, its demise was a long and slow process of dwindling returns. With the coming of the car, roads opened up, and the highways took a more prominent role in transportation. As passengers dwindled, the railways began feeling the pinch. This can be seen in an article found in the Enterprise Bulletin in January 1950, stating that the CNR would be cutting the noon train three days each week. “The taking out of service of these trains is hoped to be a temporary curtailment only, and is said to be the result of a shortage of soft coal now being felt in Canada. When coal again becomes more plentiful, it is expected that these trains will be put back in service.” Cars, not coal, it seems, would be the lasting cause of the train’s curtailment.

By the mid-20th Century, only the mail and freight service made the railway lines financially viable. This too changed when transport trucks travelling on the improved highways took over the mail and freight deliveries, and the railways across the country began to close down.

The trains stopped running on October 29th, 1955, on the Creemore route (also known as the Hog Special), and the tracks were removed between Alliston and Creemore shortly thereafter. Freight service to Glen Huron and Creemore continued via Collingwood for another five years before the tracks laid down in 1877 were pulled up on September 30, 1960. The passenger service also continued between Allandale, Collingwood, and Meaford until that fateful Saturday in July of 1960. The Collingwood station remained in use up until that time. Once the station was no longer needed for passenger service, the building was closed, and its offices were moved to the north end of the Freight Shed at the corner of St. Paul and Simcoe Streets.

In an interesting, if short-lived attempt to revitalize train traffic, a group of local residents concerned with the railway’s depreciating value to the Town of Collingwood convinced the Canadian National Railway to start passenger service on Sundays for skiing enthusiasts. From January 5 to March 8, 1963, trains left Toronto’s Union Station at 8:00 a.m. and arrived back at 8:00 p.m. Prices, including ski lift tickets to Georgian Peaks, Blue Mountain, Devil’s Glen, and Alpine Ski Club, were $7.75 for adults and $5.90 for children under 12. Although successful, the “Ski Special” was discontinued in 1964 due to inclement weather conditions and inflexible schedules.

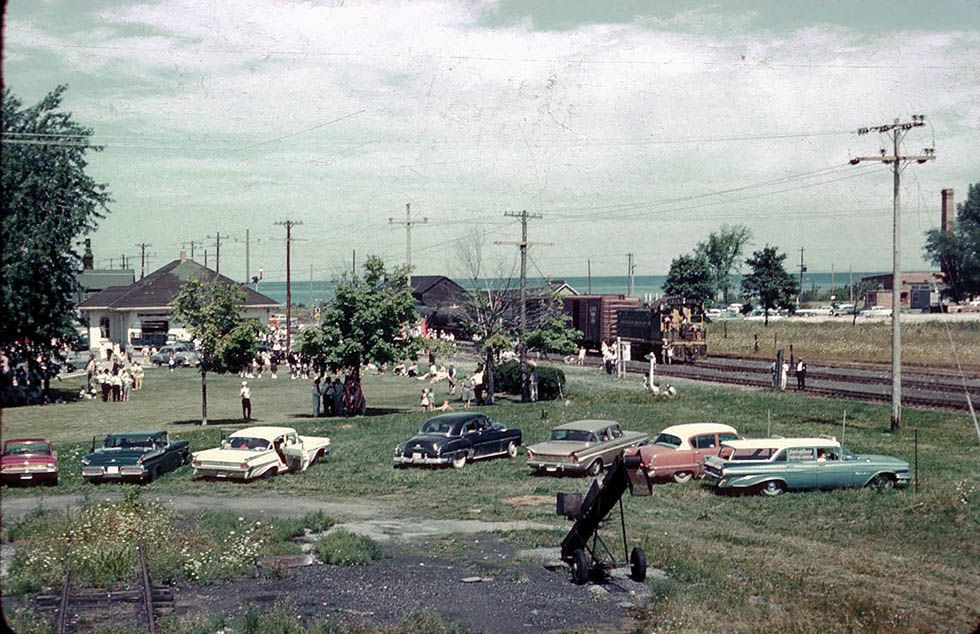

Derry Day celebrations on the Collingwood station grounds, 1962.

Photographer, Peter Coates. Collingwood Museum Collection, 998.23.3.1e

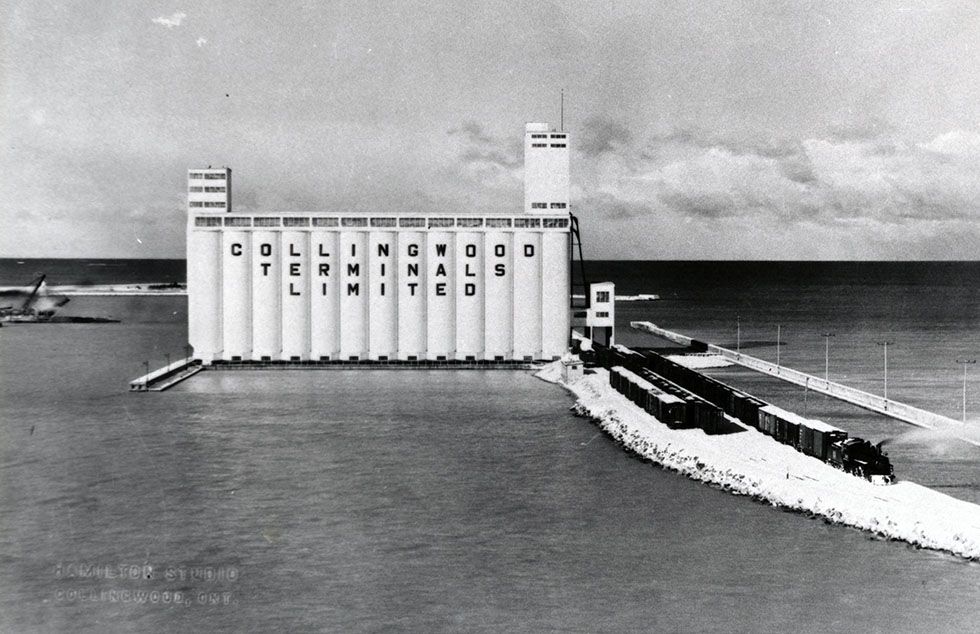

The grain train at the Collingwood Terminals, c. 1930.

Photograph by Hamilton Studio. Collingwood Museum Collection, 994.2.1o

The railway office was still very busy with the daily way freight between Allandale and Meaford, and the CNR continued running freight service to the Collingwood Shipyards right up to the build of the last ship in the mid-1980s. There was a rail siding into the steel stockyard where very heavy loads of steel were unloaded. Rail sidings also went into the Machine Shop on Huron Street and the Boiler Shop behind the Mountain View Hotel, but the steel stockyard was the critical one because of the heavy tonnage.

As J.T. MacMurchy wrote in 1963, “One by one, the many services gradually passed away until we are now left with the skeleton of what was once a booming industry.” By the early 1960s, it was plain to see that most shipping was moving away from the Great Lakes to coastal ports and the St. Lawrence. Demand for Great Lakes ships was on a steady decline. The decision was made to diversify the industrial base of Collingwood, drawing new manufacturers into the area. This project was very successful, and by 1967, eight new industrial companies called Collingwood home, several of which made parts for the increasing automobile sector.

These new factories located in the East End Industrial Park of Collingwood also needed a railway spur to take their products to market. This resulted in the development of the Pretty River Industrial Spur, which was officially opened on November 22, 1967. The need for the line was a testament to the industrial growth of the community. It serviced the industries of National Starch, Barton Distilling, and Libbey-Owens-Ford.

A commemorative train trip was run in 1979 by the CNR and sponsored by the Upper Canada Railway Society, celebrating 125 years of passenger rail service. This was powered by the steam locomotive 6060, nicknamed “Bullet-Nose Betty,” for the shape of the front of the boiler where the headlight was mounted. But despite the nostalgic celebration, on December 31, 1985, the CNR abandoned the line, and the concept was formulated to take out the rails between Collingwood and Meaford and create cycling paths, as had been done already in Ottawa.

By 1990, there were only two trains a week which served local industry. The freight trains through Utopia continued to provide service for Canadian Mist and NACAN in Collingwood.

Beyond these many attempts to revitalize the dwindling railways, other less conventional schemes had been proposed through the years to keep the railway’s original importance as a part of Collingwood. As recorded in “The Story of Collingwood: 100 years 1858-1958” (published for the town’s centennial), some of the more interesting ideas floated included building a ship railway from here to Lake Ontario—think Lock 44 on the Trent-Severn Waterway, the Big Chute marine railway. Only this proposal would have seen one built that would be over 100 kilometres long. The proposal was for fully loaded vessels to be lifted out of the northern waters here, then placed on rail cars, and then finally dropped into Lake Ontario once again. Needless to say, this never got much beyond a wonderfully quirky dream.

A full-fledged ship canal from Collingwood to Toronto was also proposed to take the place of the failing railway. Not even one shovel full of dirt was ever dug. Similarly proposed was a dedicated railway freight line to be built from Georgian Bay to the Bay of Quinte at the eastern point of Lake Ontario. These and many other wonderfully weird ideas were floated through the long years of the railway’s decline, all with the same goal in mind: to avoid the long round-about lake route with a bottleneck in the canal across the Niagara Peninsula. But in the end, it was the cars and trucks and roads and highways that won out.

Engine No. 1, the Lady Elgin, was the first engine to arrive in Collingwood on January 1, 1855. Collingwood Museum Collection, X976.256.1

Ski train with Georgian Peaks in the background, 1962.

Photographer, Peter Coates. Collingwood Museum Collection, 998.23.3.9d

Members of ‘A’ Company, 157th Battalion, leaving Collingwood for Camp Borden by train on July 2, 1916. Collingwood Museum Collection, X2009.43.1

Looking north towards the harbour from the wooden platform at Collingwood’s train station, c. 1874-1900. Photographer, James Asa Castor. Collingwood Museum Collection, 007.19.6

And so, it was that in 1996, Canadian National Railway abandoned a portion of its rail line, including service that ran from Barrie to Collingwood. Rather than have the tracks ripped up, the two municipalities purchased 100 kilometres of rail infrastructure. This would be the very last attempt at keeping the longstanding tradition of railway service alive in Collingwood. Between 1998 and 2011, the Barrie Collingwood Railway (BCRY), operating under Canadian Pacific Railway, serviced customers in Innisfil, Barrie, Coldwell, Angus, Stayner, and Collingwood. But once again, over time the number of customers who utilized the rail service dwindled, and the rail era finally came to a quiet and easily overlooked end when Collingwood’s Town Council authorized the termination of rail services between Utopia and Collingwood as of July 2011.

And so, the town of Collingwood quietly went “off the rails.” What started with a literal explosion of optimism and opportunity, taking a little-known settlement by the name of Hen and Chickens Harbour and making it into an economic powerhouse overnight, disappeared with a whimper by a motion in council that simply reflected the sad reality everyone had seen coming since 1960.

But even though trains no longer provide the lifeblood for our town, the veins of those heady days still lie at the heart of our town for those who know where to look. The Collingwood Museum and its grounds, the Terminals, and so many street names still bear the marks of that locomotive history. Now you can walk, jog, or bike those old train tracks all the way from Stayner to Meaford and through all parts of Collingwood. Many of our most popular trails are those old train lines, repurposed for human-powered travel. On some parts of them, you can still see portions of the tracks and reflect on the long history they carried. For our history as a town was built on those tracks. And it is a history full of so many stories that will have to wait for another day. E