The Waubuno, operated by the Collingwood-based Georgian Bay Transportation Company, was a familiar sight in Collingwood’s harbour. On November 22, 1879, it departed during a storm and was tragically lost with all hands. Collingwood Museum Collection, X969.622.1.

Fit to be Tied

Script by Ken Maher, Stories from Another Day, a Collingwood Museum Podcast. Photos courtesy of the Collingwood Museum.

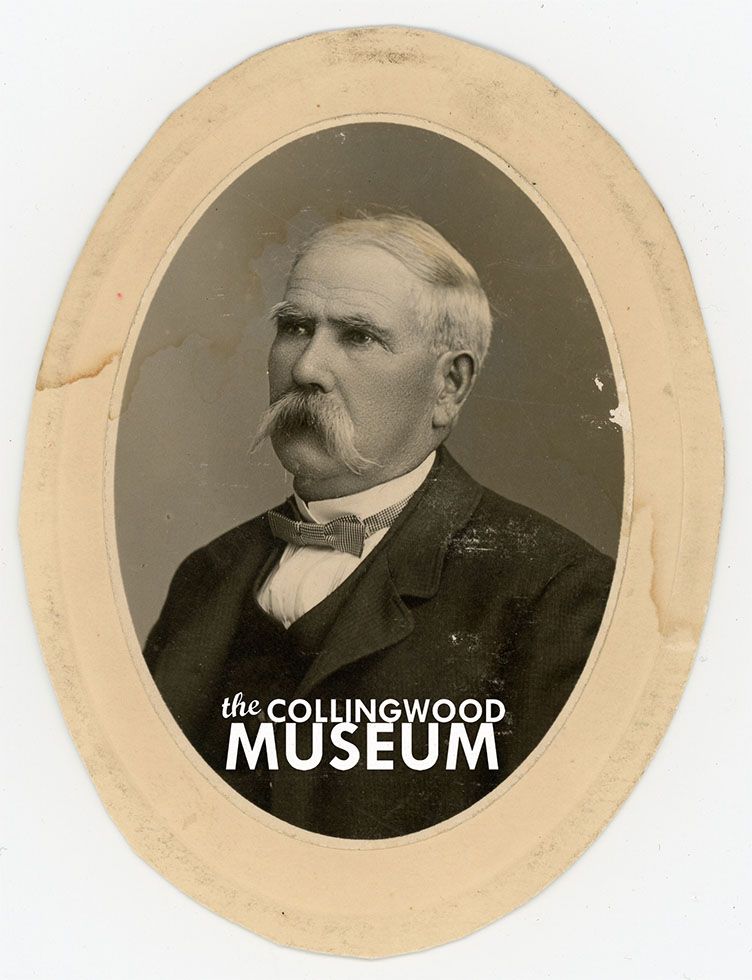

A notorious night on the steamer Waubuno in 1875 sealed the fate of Collingwood’s chief constable, John Creelman, whose troubles with alcohol and the law ultimately led to his downfall.

“Hello, Creelman!” said the mocking voice. He emphasized the derision with a rough jab of his toe. The pitiful bundle on the deck at his feet could only squirm and moan quietly. As the deck of the ship swayed in the gentle swells of the bay, the bound-up form rolled across the planks and back again. “Excuse my feet,” came another voice, a woman’s. While the kick was softer this time, the toe of her shoe was more pointed. The helpless man could only gurgle his displeasure weakly. It had been going on like this all night, and no one seemed ready to take pity on him. “Why didn’t I jump overboard when I had the chance?” he thinks to himself for the hundredth time.

It is a warm August evening in 1875 on the steamer Waubuno, whose sad end was marked by… well, that is a story for another day. But on this day—or night, rather—the Waubuno is heading from Collingwood to Christian Island to deliver her passengers to a church camp meeting. And the man deemed fit to be tied and left on the deck to the less-than-Christian actions of the passengers? His name is John Rutherford Creelman, and he is the chief constable, town inspector, and tavern inspector of Collingwood. And, in case you missed it, he is not well-liked or respected.

From left: A small brick jail once stood behind Collingwood’s town hall, visible in this 1896 photo behind Captain George Collins, former Nottawasaga Lighthouse keeper. Chief Constable Benjamin Franklin Lewis, who succeeded John Rutherford Creelman, was the town’s first full-time chief, holding the role for 21 years. Collingwood Museum Collections X976.575.1, X2025.1.1.

In fairness, it should be said that his was a tough job in a very tough town—a job that will make enemies no matter what you do. In fact, his predecessor, Constable Thompson, had lasted only several months in the post. Resigning suddenly while embroiled in scandal and facing serious allegations, the town council was forced to choose a new replacement with great haste. Their choice was John Creelman. He was chosen in large part due to the respect so many locals held for him. Maybe this was a way to appease the people over the former chief ’s shortcomings. The 55-year-old Creelman was a local music teacher, noted as being both knowledgeable and talented. Yet much of Constable Creelman’s troubles on the job were of his own making.

Maybe he let the pressures of the job get to him, or maybe he would have been that way regardless, but John Creelman’s troubles as constable began and ended in the bottle. The first angry rumblings against him came not long after his appointment in 1873, when it was alleged that, while drunk, he had mistreated a man by the name of Ralph Smith. When a committee tasked with investigating the claim went to speak with Smith, he was too sick to answer and died soon after. Officially, Creelman was cleared, but the whole affair left many people soured toward the chief constable.

From left: The Collingwood Police Department’s insignia featured a shield with symbols representing the town—a ship, fish, and ski equipment. This pin was worn by Sergeant Donald McQueen, who joined the force in 1956. Collingwood Museum Collection, 2014.16.1.4.

The North American Hotel, built in the 1850s on the east side of Hurontario Street, offered stagecoach service between Durham and Collingwood. As the sign suggests, a public “Bar Room” welcomed travellers and locals alike—one of many spots in early Collingwood where whisky flowed freely. Collingwood Museum Collection, X969.817.1.

Creelman was well-known to inspect the taverns of Collingwood by being one of their most faithful customers. It was widely known among the town council that everyone in town took great pleasure in obstructing Creelman, and the town was going to the dogs because of it. And on the night of the church camp meeting, it seems Creelman was drunk once again, and the good people of Collingwood had had enough of it.

To quote Larry Cotton in his book Whiskey and Wickedness: Volume 4: “When Creelman’s sobriety was questioned by a fellow passenger, the chief constable, with that true heroism which marks the gentleman, had the courage to resent the insult hurled at him.” His fine, slurring words did him little good. In short order, the unsympathetic passengers found some old sail with which to wrap and bind him before rolling him unceremoniously around the deck. After their sport, Creelman was let go, only to be once again caught and tied up, this time for the remainder of the night and the near-constant obstacle of everyone’s unforgiving feet.

In fairness, it should be said that his was a tough job in a very tough town—a job that will make enemies no matter what you do.

Yet not even this ridiculous episode spelled the end for Creelman. This would come a year later at the hands of another person named Smith. The chief constable would finally lose his job when a very well-known brothel owner, Mrs. Smith, became involved. But not for the reasons you might think. She had been arrested on charges of keeping a house of ill-repute in August of 1876. During the three-day trial, many of the townsfolk claimed to have no knowledge of Mrs. Smith or her bawdy house, yet everyone agreed it seemed that there were far too many such establishments in town, and Constable Creelman had done precious little to close them down.

The Collingwood Police Force was composed of at least four men in 1915. From left to right: Constable Fred Bendell, Chief James Johnston, and Constable Arthur Plant. Constable William Butters is reported to have been missing from the group photograph. Collingwood Museum Collection, 999.14.2.

Mrs. Smith was convicted and sentenced to six months in the county jail in Barrie. Chief Creelman was given the task of escorting the prisoner to jail by train. Upon hearing this, Mrs. Smith thanked the court and promptly boasted that she was sure if Constable Creelman was in charge of getting her there, she would never see Barrie. And she was right.

No sooner had the train left the Collingwood station than Creelman found himself, as habit would have it, in the bar car, letting the infamous madame roam the train at her own leisure. He would later insist that he was only reading at the time. When the train stopped in Stayner, he discovered too late that Mrs. Smith had escaped his “watchful” eye by disembarking at the very first stop in Batteau. She was never seen again in these parts. But John Rutherford Creelman was seen that very night back at the town council meeting where he had to explain why he wasn’t in Barrie. The council was livid. Fit to be tied. After a very brief debate, Creelman was dismissed on August 22, 1876, and a new chief constable was appointed on the spot.

Clockwise from above: This hand-painted sign once hung outside Collingwood Police Department offices on Hurontario Street. This key, believed to have been used for Collingwood’s first jail, was donated to the museum in 1966. David Swain carried this leather-covered billy club during his service with the Collingwood Police Department around 1906. Collingwood Museum Collections, 999.22.1, X976.569.1, 2010.22.1.

As author Byron J. Montgomery writes in Duty and Dedication: A History of the Collingwood Police Force, “[a]n era ended in the history of the Collingwood Police with Creelman’s discharge. The age of the part-time policeman came to an end, as the council realized the town’s need for more professionalism and dedication in law enforcement.”

And what happened to Creelman? Very little is known, except a trail of additional hardships that no doubt affected his ensuing years. In 1876, just prior to his dismissal, one of his daughters died at the age of 25. Four years later, he lost his wife, Isabella. By 1881, Creelman and five children, ages 10 through 18, had left Collingwood, relocating to a farm on the eastern boundary of Collingwood Township (today’s Blue Mountains) in the vicinity of Scenic Caves Road. One hopes that his relocation from town life brought some peace to the remaining years of his life. E