Photo by Clay Dolan

The Light at the End

of the Tower

Script by Ken Maher, Stories from Another Day, a Collingwood Museum Podcast.

Photos courtesy of the Collingwood Museum.

From its construction in the 19th century to the efforts that continue to preserve it today, the Nottawasaga Lighthouse reflects the spirit that has shaped Collingwood’s vibrant heritage.

Already, the woman’s arms were burning with the effort. The wheelbarrow was getting heavier with every laboured step. When the tire hit an exposed rock and the whole thing tilted wildly to the side, she took it as a sign to stop, catch her breath, and shake out her aching muscles. It also gave her a moment to observe the man folded into her makeshift litter. At the bump against the rock, he had moaned and taken in a sharp breath. His quickly greening face was perspiring more than hers. She gave him a reassuring caress and lifted the wheelbarrow and the man inside it once again. A cacophony of birdcalls rose from the surrounding trees and bushes, several flying into the air with staccato cries of avian judgement. But her eyes were firmly focused straight ahead. Thank the heavens above, she thought to herself, the rough path across the small island was nearly over. She could see the dock up ahead.

But that only brought new problems. After much struggling, groaning, and a muttered curse word or two, she somehow managed to get the man into the awaiting boat, the effort causing him to retch and heave overboard. She understood just how he felt. “Stay with me, Jim! I need your help now. You know I don’t know how to get this infernal motor to start.” With a hint of his old smile, her husband looked up and said, “You can do this, Doris.” And with his halting instructions, she did. In short order, the bumpy wheelbarrow ride turned into a choppy boat ride, Doris opening the little boat’s throttle as wide as she dared. It was only minutes to cross to shore, but it seemed like an eternity, with each new jostle and bounce turning her husband’s face greener and greener. He needed help, and soon.

Then the waters smoothed, and they reached the shore of White’s Bay. And that is when the realization hit her like a thunderclap. The wheelbarrow was still back on the island. How was she supposed to get him from the boat all the way up to the car? He was having trouble even sitting upright. Fighting back the tears, she took a deep breath. She could do this. Her husband wouldn’t like what came next, but it had to be done. “Alright, Jim, you need to get on my back,” she said. “I’m going to carry you to the car.” The look of shock only registered on his face for a moment. He knew she was right. “You can do this, Doris,” he said again. “I trust you.”

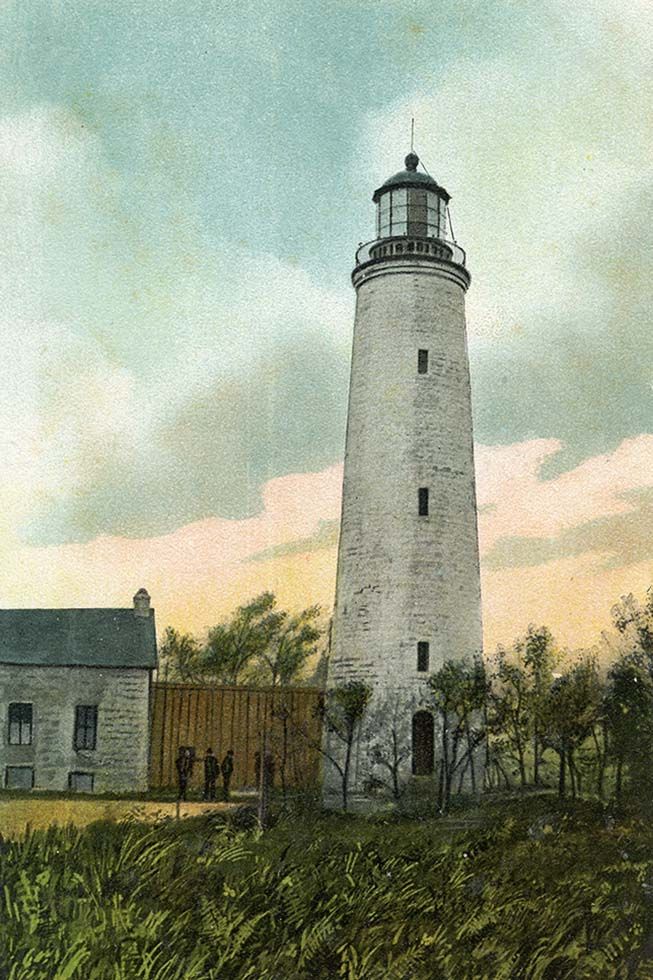

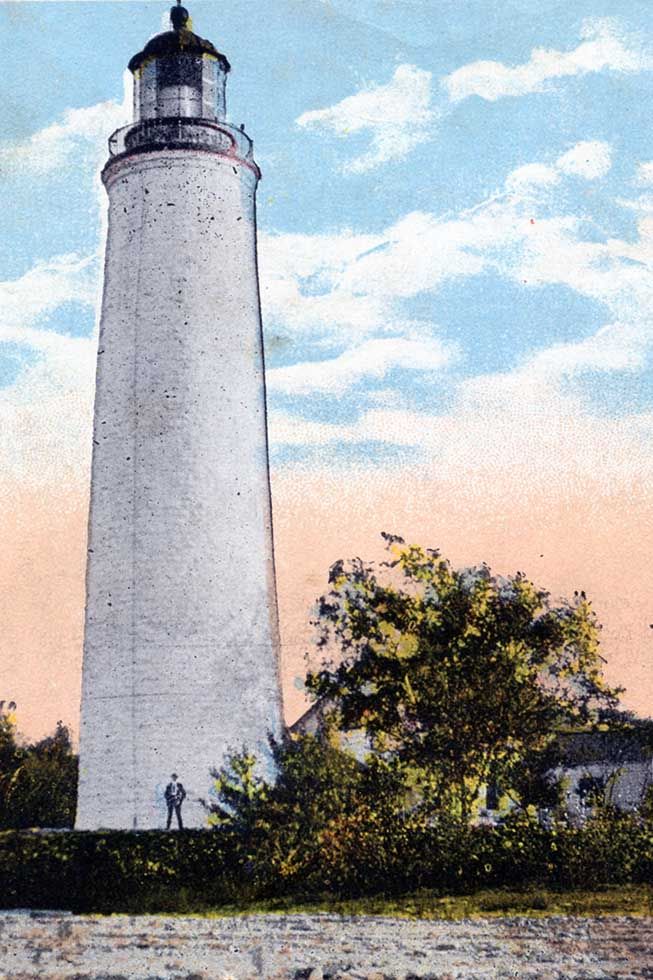

Nottawasga Lighthouse postcard (Collingwood Museum Collection, 006.20.31)

The original Nottawasaga Lighthouse and the lightkeeper’s house. Photo: Nottawasaga Lighthouse Preservation Society.

Jim Keith, the local keeper for the Nottawasaga Lighthouse from 1952 to 1956, avoided an untimely fate and, with the help of his wife, Doris, made it to the hospital in time to have surgery for appendicitis. And that day, while a memorable one, was not altogether unprecedented in the long history of our town’s lighthouse and the lives and stories of the 15 men and their families who kept safe both our community and the hundreds of thousands of Great Lakes travellers over its 124-year sentinel along our rocky shores.

With the opening of the Bruce Peninsula, the influx of settlers, a free trade agreement with the United States signed into law in 1854, the opening of the Sault Ste. Marie Canal, and the completion of the Collingwood Toronto railway in 1855, the need for navigational aids on a much busier Great Lakes became an urgent undertaking. And so, Collingwood’s Nottawasaga Lighthouse is one of six Imperial Towers built on the Great Lakes between 1855 and 1859.

And they were completed in a singularly grand fashion. The book “Keepers of the Light” by Marion E. Sandell details both the construction and the workings of the towers. Each of the lighthouses was constructed of dolomite limestone, our own building being between six and seven feet thick at the base, which narrows steadily toward the top, where it is only two feet thick. Each tower was then capped with granite to support the weight of the French-built, red cast-iron lantern room. Each tower was whitewashed upon completion. Another unique feature of the building was unseen from the ground—gutter drains in the shape of a lion’s head used around the dome of the lantern room.

Records from the Collingwood Public Library indicate that the Nottawasaga Lighthouse was built at a cost of $14,120. But the full cost of a tower, a keeper’s house, and the attendant buildings fell in the range of $32,000 to $37,000 for each of the Imperial Towers, depending upon their locations.

The Nottawasaga Lighthouse began its operations on November 30, 1858. It stands an impressive 86 feet in height, and in its day, the light it gave off was visible for 17 miles (or 27 kilometres). From April to December every year, year in and year out, this light rotated consistently from sunset to sunrise. It required weights in the tower to be wound up every four and a half hours. The whole process of lighting up and closing down the lighthouse each day took about 20 minutes every evening and another 20 minutes every morning (Sandell, p. 19).

Clockwise from top left: Nottawasaga Island Lighthouse and keeper’s house, summer of 1936 (Collingwood Museum Collection, X968.896.1); Lightkeeper Captain George Collins, 1896 (Collingwood Museum Collection, X976.575.1); A piece of planking recovered from the wreck of the steamer Mary Ward, wrecked on the shoal now of that name in November 1872. The planking, currently on display at the Collingwood Museum, was donated to the museum in 1966 (Collingwood Museum Collection, X972.685.1).

Each of the Imperial Towers was fitted with a lighting apparatus manufactured in Paris, France, by the Louis Salter Company. These were brought overseas by steamer before being conveyed to Collingwood on the Northern Railway. From there, they were shipped out by steamer once again to the various lighthouses, ours only having to go a very short distance. When they arrived at their locations, a French crew of technicians was needed to assemble the lantern rooms and attendant equipment.

“Initially, sperm whale oil, delivered in fifty-gallon casks, fuelled the Argand lamps. But the keepers grew dissatisfied with the poor quality of the flame produced from the oil.” These lamps would be replaced in 1868 “with the invention of Doty’s Patent, a lamp invented for the burning of petroleum oils.” This not only burned cleaner but cut the cost of fuel for the lighthouses significantly (Sandell, p. 2). In addition, popular opinion backed the decision as nine out of ten sperm whales wholeheartedly supported the move to the new fuels.

Originally, eleven Imperial Towers were planned, but only six were built. Why the name “Imperial” applied to the towers is not known. “A 1991 federal report on heritage buildings suggested funds from the Imperial treasury were necessary for their completion” (Sandell, p. 1). This may also explain why only six of the eleven were finally built. These six lighthouses ended up being placed on Point Clark, Chantry Island, Cove Island, Griffith Island, Christian Island, and our own Nottawasaga Island. To many locals, Nottawasaga Island was known for the longest time as Clark Island, named after one of the earlier lighthouse keepers. Captain Clark was quite the character himself. It seems when he was orphaned at thirteen, he immediately decided to go out and take to the waterways, never once looking back. He began this maritime career on the Mississippi River, later sailing the Great Lakes between Buffalo and Chicago, before settling down in Collingwood in 1853 to carry mail via schooner between here and Manitoulin Island. He later ran a successful fishing business out of our harbour and then served as keeper of our lighthouse from 1890 to 1902.

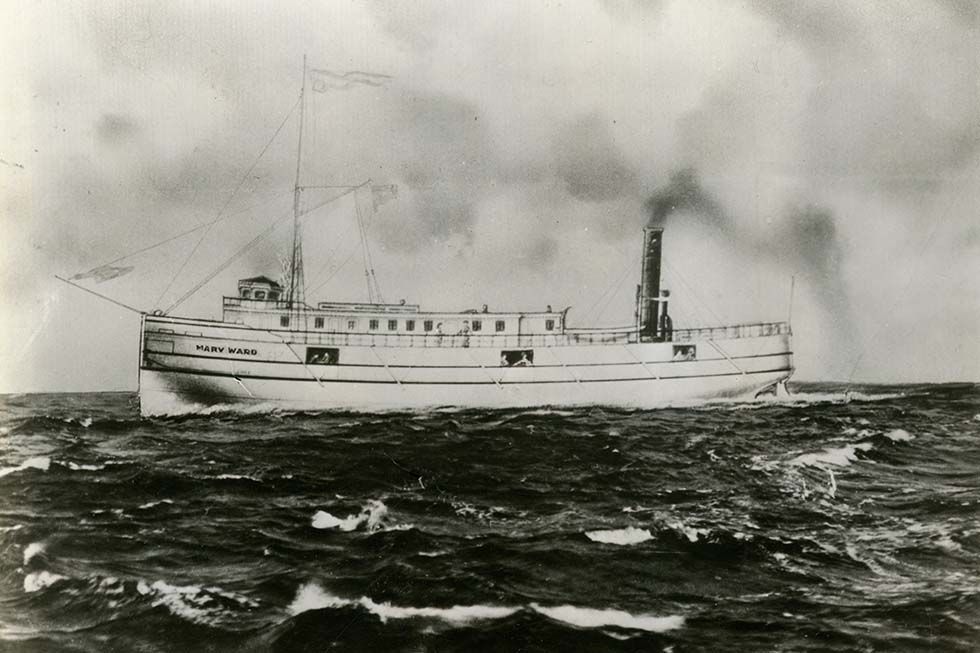

Clark Island, or Nottawasaga Island as it is now known, is about five acres in size, and is part of a series of reefs and shoals paralleling the shore of this section of Georgian Bay that is, of course, one of the key reasons a lighthouse is necessary in the first place. Just south of Nottawasaga Island is a much smaller island often, and appropriately, named One Tree Island. Can you guess why? These, however, are just the most prominent of the reefs and shoals which also include Lockerbie Rock and the Mary Ward ledges, the latter being named after the marine disaster where… well, that is a story for another day. But on this day, as we talk about the lighthouse and her keepers, I can tell you that the lighthouse keeper at the time, one Captain George Collins, helped to rescue 24 people that day. And this was only a small sampling of the 52 lives he is credited with saving over his nearly 32 years of service at the lighthouse between 1859 and 1890. It was also under his tenure as keeper that a miscommunication from the lighthouse nearly set off a panic in town, with the residents thinking they were being invaded by Fenians. We talked about this in Season 1, Episode 7: “No Shot in the Dark.”

The only known depiction of the steamer Mary Ward in the Collingwood Museum’s collection. The ship ran aground on Milligan’s Reef (later renamed Mary Ward Shoal) in November 1872 (Collingwood Museum Collection, X974.496.1).

While the lighthouse keepers served for the safety of those on the bay, there was little way of a safety net for them. Just ask Doris and Jim. When the situation got bad, you were on your own out there on the island. See, the whole time the lighthouse was manned, all 124 years of it, there was no communication system on the island, no running water, and no electricity. The house was heated with wood chopped from dead trees on the island or from driftwood collected throughout the year. Wives and children of the lighthouse keepers would often join their husbands and fathers on weekends or through the summer months, but otherwise it was a very lonely business. It was a job that could be done by only the hardiest and most self-sufficient individuals and their families.

But life on the island was not without its perks. It was a lovely place for children to grow up in those beautiful summer months, and so many of the lighthouse keepers’ children spoke of fond memories of exploring the island, of summers spent swimming, boating, and fishing. It was particularly popular for Sunday visits, for tours and picnics, with plenty of townspeople providing so much company at times that the quieter days in between were not nearly so lonely.

A fire badly damaged the keeper’s house in 1958, and only parts of it were rebuilt. You see, by that time, the writing was already all over the whitewashed walls. Marine technologies were continuing to advance at a rapid pace, and the need for lightkeeping had become obsolete. The Nottawasaga Lighthouse, now maintained by the Canadian Coast Guard, would be fully automated in 1959, requiring a new kind of caretaker. One that didn’t need to live on the island. The keeper’s house, abandoned for many long years, was torn down in 1971. Eventually, the lighthouse itself was decommissioned in 2003, and in 2004 it was struck by lightning and damaged. Banding was placed around it to slow the effects of the damage, but in 2010 the Coast Guard ceased any further maintenance of the Nottawasaga Lighthouse, leaving its future existence as a local landmark very much in doubt.

Since humans no longer reside on Nottawasaga Island, it has become an important bird sanctuary. But that doesn’t mean that the people of Collingwood are ready to see the abandoned tower disappear. As detailed on their website, the Nottawasaga Lighthouse Preservation Society was incorporated in 2015 as a volunteer-run, not-for-profit organization dedicated to the restoration, preservation, and protection of the historic Nottawasaga Lighthouse. Their mandate is to protect the important architectural and cultural significance that makes the Nottawasaga Lighthouse such a significant part of Canada’s Great Lakes marine heritage not just for us in Collingwood, but for the benefit of all Canadians.

The Society, they further state, hopes to acquire and restore the Nottawasaga Island Lighthouse, eventually reconstructing the lightkeeper’s residence. This will help ensure that the heritage resources of the Lighthouse are protected in a manner that respects their significant and irreplaceable historical legacy.

I don’t think it would be an overstatement to say that the railway, the shipyards, and the lighthouse all worked together to create and sustain our vibrant town, and without any one of them, who knows how different the story of Collingwood may have been. The railway has disappeared, the shipyards are long since closed, but the lighthouse still stands as a beacon to our town’s vital marine history. Through the dedicated efforts of those whose hearts burn like the dedicated lighthouse keepers of old, perhaps there is a hopeful light on our Imperial Tower’s horizon once again. E